Special to WorldTribune.com

By Dr. Assad Homayoun and Gregory Copley, Editor, GIS/Defense & Foreign Affairs

Iran, no less than the European Union or the United States of America, faces a series of problems which place it at a critical strategic junction. It now faces urgent challenges, the response to which will determine its viability — even its survival — over the coming decades.

The U.S. thinker Hans Morgenthau said, in Politics Among Nations: “Never put yourself in a position from which you cannot retreat without losing face, and from which you cannot advance without grave risks.” Iran has allowed itself to be put in this position, and — with regard to a potential conflict with Iran — Israel and the United States have also allowed themselves to be put in such a position, albeit not so gravely as Iran.

Iran has traditionally been surrounded by hostile, or competitive, forces. In the past century, Iran was contained and constrained by the Russian Empire and then the USSR to the North; by the Ottoman Empire and then Iraq to the West; by the British, and then the Taliban, to the East; and by the Sunni Arabs and British to the South. This mold broke apart with the collapse of the USSR, the defeat of the Taliban, the destruction of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and by the ongoing strategic weakness of the Arabian states. This latter situation in the Persian Gulf was accelerated by the withdrawal of the, and then — in 2011-2012 — by the de facto withdrawal of the U.S. (or of U.S. influence) which had replaced Britain as the Gulf external power.

This confluence of events provided a unique alliance of the stars for Iran. But Iran lacked the leadership, efficiency, and vision to take advantage of that respite from the chains which bound it. In part, this situation — this inability to seize the situation — has been based on Iran’s failure to evolve from the overthrow of the Shah in 1979. The clerical leadership of the State has sustained an approach to governance and statehood since that time which has not evolved to create a national grand strategy which could help it assert Iran’s, or Persia’s, traditional geopolitical vision.

That is not to say that Iran’s clerics have failed to instinctively take paths which have been traditionally Persian in a geopolitical sense, but that they have not done this with any real understanding of history. Moreover, the clerics have attempted to use religion — Shi’ism — as the “carrier wave” and justification of all of its activities, both domestic and foreign. This has hampered the ability of Iran to take full advantage of its situation, and left it by 2012 as almost a vassal of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Iran has, in many respects, been unable to develop viable strategic and foreign policies because it has not yet resolved its domestic governance in a way which guarantees efficiency, or popular support for the State. The clerical government has, essentially, failed (or refused) to draw upon and galvanize traditional Persian culture, values, and loyalties, but instead has attempted to make Shi’ism the sole process of legitimacy and governance. Again, that is not to say that the clerical government has failed to take foreign, military, or strategic steps; it has, but many of these have been reactive or have been undertaken outside of a valid strategic context, and lacked the force and efficiency required to make them effective.

Domestically, there is little unity and little cause for optimism. The economy is in tatters, and not merely (or even mainly) as a result of the U.S.-led trade embargo against Iran. Inflation is at destructive levels: officially it was 21.5 percent in urban areas for the year-ending March 19, 2012; in reality it is clearly much higher than that (The Economist in July 2012 claimed it at around 30 percent) 2. Unemployment is high, reaching 35 percent in some urban areas as of mid-2012.

Iran’s oil exports — its major source of foreign exchange earnings — declined by some 50 percent between February and June 2012, but stabilized at that point. They were expected to average 1.084-million barrels per day (bpd) in July 2012, only a fraction down from June, as a result of an increase in PRC oil imports from Iran. [Only four major clients existed for Iranian oil in July 2012: the PRC, India, Japan, and the Republic of China (ROC: Taiwan).] An EU embargo on oil purchases and shipping insurance on traffic to and from Iran came into force at the start of July, and even Turkey — which is, of course, outside the EU embargo framework — cut back sharply on Iranian oil purchases.

Thus, with or without sanctions, the economic malaise in Iran has worsened to the point where social and political consequences internally seem inevitable. The situation has been hampered by relative mismanagement of the economy, or at least a lack of direction within it. Again, this is not to deny the reality that the government has attempted to undertake industrial and commercial projects, but these have been hampered by the lack of a domestic economic and political strategy, and by rampant (although possibly declining) corruption within the government.

All of this, however, has been symptomatic of the real weakness in the Iranian structure: the lack of coherent, singular leadership. This, too, has been symptomatic of the failure of the clerical Government since 1979 to build a broad base of popular support. Rather, it has been successful only at the suppression of opposition, and even when popular unrest has spilled into the streets — as it did with the 1999 student uprising, and the 2009 open unrest in almost all cities — even the opposition has lacked leadership.

The success of the clerical Government in suppressing unrest has been achieved with significant support and assistance from the Russian and PRC governments. As well, the clerics can be said to have successfully diverted the popular unrest by having clerical adherents, such as Mir-Hossein Mousavi Khameneh and Hojjat-ol-Islam Mehdi Karroubi, emerging as “opposition” leaders to channel the unrest into a powerless stream. These so-called opposition figures were not even the other side of the same coin as the clerical leadership; they were the same side of the same coin.

In all of this, Iran has become increasingly dependent — as it is for trade and protection — on the PRC and Russia, despite the significant resentment of Moscow by the Iranian leadership, and the growing resentment against PRC dominance of the domestic economy by many Iranians.

An extensive body of opposition to the ruling clerics exists within the four- to five-million Iranians in the diaspora, but even though the expatriate Iranians have the freedom to remain engaged in debate about the future of their country, they lack cohesion, leadership, and a vision of their demands. Thus they remain ineffective in acting as a voice for Iran, or against the clerics. The result is that most major power policies toward Iran are made without reference to the vast expatriate body of knowledge on the country. This is in distinct contrast to, for example, the effectiveness of the anti-Turkish activities of the diaspora Armenian communities of North America, Europe, and Australasia.

The key bridge in this, and in any discussion about Iranian strategic outcomes and activities, is the Revolutionary Guard (Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps: Pásdárán). The Pásdárán is the dynamic element in the Iranian political equation, even though this force of some 250,000 armed personnel is not a unified or single-faceted body. The clerics are, essentially, now subject to the power of the Pásdárán, the creature of their own making. If leadership emerges from that armed body, it could drive changes in Iran.

Indeed, the Quds Force of the Pásdárán is already the key element of Iranian strategic projection, both with regard to its intelligence capabilities, its control of formal and informal non-Iranian forces outside the country, and with its own covert paramilitary functions. Pásdárán also controls Iranian strategic weapons: the ballistic missiles and the existing nuclear warheads. The question, then, is whether the Revolutionary Guard will continue to support the clerical leadership, particularly as that leadership weakens and becomes increasingly engaged in fratricidal internal conflict.

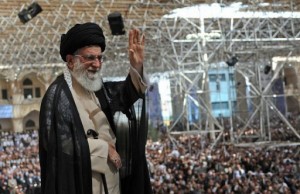

As we bridge the analysis from the domestic situation to Iranian foreign and strategic policy, it is worth noting that “Supreme Leader” Ayatollah Ali Hoseini-Khamene‘i and President Mahmud Ahmadinejad are becoming progressively weaker.

Ahmadinejad is now, politically, almost powerless, and even at the height of his “power” — as perceived by external analysts — he was never in a position to overrule the Revolutionary Guard, even as he attempted to put his own supporters in positions of authority within it. The “Supreme Leader” is in declining health, and also, arguably has (and based on observations of his activities in 2012), lost his political legitimacy and sense of leadership.

Given the stalemate in the domestic political situation, with regard to the economic and social situation, as well as the feeling of isolation which is now becoming pervasive within the community, it would not be surprising if elements of the Revolutionary Guard sought to exert their power. The clerics’ only hope is that the Guard itself is not cohesive, and has mutually competitive elements. There is definitely a growing body of thought within Iran that the isolation cannot continue indefinitely, and that the longer it continues the greater Iran’s subservience to Russia and the PRC — and dependency on North Korean weapons — must become.

Significantly, there is surprisingly little hostility among Iranians toward the West, and even the U.S. and Israel, despite the decades of propaganda by the clerics. It is generally acknowledged that most Iranians would prefer normalization of relations with the West, including Israel, rather than dependency on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states, dominated by Russia and the PRC.

These are critical considerations as the Western media, and some politicians, consider the “inevitability” of a U.S.-led or Israeli-led war against Iran over the issue of Iran’s acquisition of a domestic nuclear weapons manufacturing capability. The reality, when the long-term structural architecture of Iran and its population is concerned, is that Iran does not pose an “existential” threat to Israel, for example. Iran has not, for the past 250 years, initiated war against any state, and even the late 20th Century Iran-Iraq war came directly as a result of conflict initiated by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. Moreover, the past 2,500 years have been dominated by a bond between Iran and Israel, which has been as much a geopolitical strength for both as it has been a cultural bond. Both modern states, in fact, see a common cause for concern in the hostility of the Sunni Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and (lately) Qatar.

Bearing on this is the reality that the Israeli Government led by Benjamin Netanyahu (Likud Party) was, on July 17, facing a considerable weakening, as the Kadima party quit the Coalition Government in a dispute over drafting ultra-Orthodox Jews into the military. The Government was not expected to collapse because Likud still had a majority in the Knesset, but the issue took away a little of the government’s ability to stake the country’s future on proposed military action against Iran. Indeed, increasingly, Israeli officials have been speaking out against military action against Iran. [Nonetheless, Kadima was likely to return to the Coalition; it has nowhere else to go.]

In terms of foreign policy — as a subset of strategic policy — Iran has been running more-or-less on fumes. Its basic approach of mobilizing the Shi’a populations of the region has been relatively successful, and this has extended to its relationship with Syria, at present dominated by an ‘Alawite (essentially Shi’a) minority Government. This policy approach of building a stepping stone path of Shi’a communities linking Iran with the Mediterranean has, however, dramatically reinforced Sunni-Shi’a antagonisms, and, arguably, has served to help reinforce the radicalization of the already-fundamentalist Wahhabi sect of Sunnism and its jihadist approach toward competing with Iran in Syria and other areas.

Again, this has been caused by the transformation of traditional Iranian geopolitical visions, subordinating them to being conducted through the vehicle of Shi’a religious projection. Iran has always had a sense of belonging to, and participating in, the Mediterranean. Its links with the Levant, including ancient Israel, as well as its forays toward Greece, are native to Persian geopolitical thinking. The Islamicization of this process, however, has reduced the pragmatic nature of Iranian foreign policy, and this Islamicization was used to help fight against the U.S.-led war in neighboring Iraq. But this caused a schism in the historical link which Iran had with Israel. The clerics in Tehran did not seem to notice this; they were oblivious to Persian historical geopolitical thinking.

Clearly, at the bottom line, if Iran loses Syria, it will be reduced dramatically in its strategic posture, and this would be directly attributable to the failure of the Iranian Government to project a tiered and textured approach toward the Mediterranean, including Israel. Even now, despite the polemics of Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, Israel is silent on the West’s (and the Sunni region’s) call for the overthrow of the Bashar Assad government in Syria. With regard to Syria — which has been a base for the major missile threat which the Iranian clerics have posed to Israel — Israel and Iran both wish to avert a Sunni revolution in Syria.

Also at the bottom line is the reality that the U.S. and Israel face the impasse which also faces Iran. All the powers have limited ability to move; they have placed themselves in a position — as has Turkey in the regional unrest — where they cannot retreat without embarrassment, and cannot advance without risk.