Special to WorldTribune, June 14, 2022

Analysis by Joe Schaeffer, 247 Real News

It is patently ridiculous when one steps back and looks at it rationally. The notion that the entire human race for some 5,000 years of documented history was completely unaware of a pressing medical issue that so dominates a human being that their mental, emotional and actual physical life depends on it being resolved. Then, in a matter of a few years, this issue becomes so prevalent that it is crosses the medical threshold and transforms into a popular culture phenomenon.

Transgenderism over the past decade or so? Yes. But we could also be talking about another fashionable diagnosis that was all the rage back in the days of disco.

Does this sound familiar today?

“I think a better way to talk about what Shirley was doing was that she was acceding to a demand that she have this problem.”

Well before there was “born in the wrong body,” American culture gave way to a bizarre social embrace of a trendy psychiatric diagnosis known as Multiple Personality Disorder.

The Shirley described above was Shirley Mason, and she was the real-life psychiatric patient who inspired the best-selling 1973 book “Sybil,” which was made into a heralded 1976 TV movie starring Sally Field.

A 2011 article at taxpayer-funded leftist bastion and enthusiastic pro-transgender kids backer NPR ably relates how a hoax became a wildly fashionable psychiatric diagnosis in the ’70s:

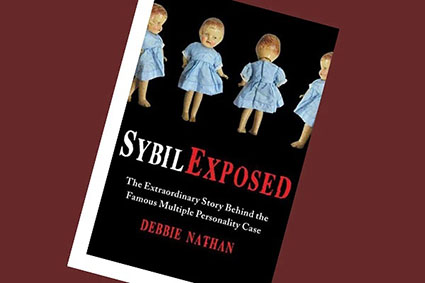

The book was billed as the true story of a woman who suffered from multiple personality disorder. Within a few years of its publication, reported cases of multiple personality disorder — now known as dissociative identity disorder — leapt from fewer than 100 to thousands. But in a new book, “Sybil Exposed,” writer Debbie Nathan argues that most of the story is based on a lie.

A desperate need for attention and a desire to please the “expert” who was providing that attention motivated Shirley’s deceit, according to Nathan:

Shirley Mason, the real Sybil, grew up in the Midwest in a strict Seventh-day Adventist family. As a young woman she was emotionally unstable, and she decided to seek psychiatric help. Mason became unusually attached to her psychiatrist, Dr. Connie Wilbur, and she knew that Wilbur had a special interest in multiple personality disorder.

“Shirley feels after a short time, that she is not really getting the attention she needs from Dr. Wilbur,” Nathan explains. “One day, she walks into Dr. Wilbur’s office and she says, ‘I’m not Shirley. I’m Peggy.’… And she says this in a childish voice…. Shirley started acting like she had a lot of people inside her.”

Under these circumstances, it’s easy to see how the self-serving “diagnosis” played out:

Mason became increasingly dependent on Wilbur for emotional and even financial support. She was eager to give her psychiatrist what she wanted.

“Once she got this diagnosis she started generating more and more personalities,” Nathan says. “She had babies, she had little boys, she had teenage girls. She wasn’t faking. I think a better way to talk about what Shirley was doing was that she was acceding to a demand that she have this problem.”

Author Nathan states that Mason tried to break away from the false diagnosis at one point, but by then an exciting new medical narrative had already been constructed that could not be scaled back:

At one point, Mason tried to set things straight. She wrote a letter to Wilbur admitting that she had been lying: “I do not really have any multiple personalities,” she wrote. “I do not even have a ‘double.’ … I am all of them. I have been lying in my pretense of them.” Wilbur dismissed the letter as Mason’s attempt to avoid going deeper in her therapy. By now, says Nathan, Wilbur was too heavily invested in her patient to let her go.

“She had already started giving presentations about this case,” Nathan says. “She was planning a book. … She was very, very attached to the case emotionally and professionally and I don’t think she could give it up. But she had a very nice little piece of psychoanalytic theory to rationalize not giving it up.”

To sum up, then: a medical diagnosis that was virtually unheard of before the mass entertainment industry glommed onto it midway through the 20th century suddenly exploded into the mainstream of public thought at the beginning of a decade in which Americans became unusually enamored with all things paranormal. With predictable consequences. From a 2015 article at Great Plains Skeptic:

Though much of the original story of Sybil was conjecture, the number of people diagnosed with the disorder after its publication soared. Prior to 1970, there were only 79 documented [Dissociative Identity Disorder, the updated name for MPD] cases worldwide. In 1986, the number of cases in the literature increased to over 6000 cases in the United States alone. There were more cases reported from 1981-1986 than in the preceding two centuries.

The fad feeds upon itself, with a DID diagnosis becoming the medical equivalent of a Rubik’s Cube purchase, only it is human life that is being played with instead of a plastic toy:

Sociocognitive theorists believe that the numbers rocketed in the early 1980s partly due to this iatrogenic effect. When the disorder gained popularity in the media, people, particularly victims of childhood abuse, began looking for the symptoms in themselves. Furthermore, therapists also began watching for the signs in their clients, implicitly prompting them into thoughts of possessing multiple personalities. This is also due in part to demand characteristics, where the client may interpret the direction the therapist is going and change their behavior to fit that interpretation.

All of this undoubtedly applies to the transgender phenomenon today. As with MPD, vulnerable persons with genuine health problems are manipulated into becoming a statistic to buttress the new fad. Tragically, the most vulnerable Americans involved in the transgender hoax are children and teenagers.

The Gateway Pundit reported June 13:

According to a new study, almost half of the 1.6 million Americans who identify as transgender are teenagers or young adults, and some of the highest rates of youth gender transition are occurring in blue states.

A study by the University of California Los Angeles Williams Institute found that gender transition rates differed between the states. New York led the pack with a 3% rate among youth, while Wyoming came in at only 0.6%.

Just as with MPD some four-plus decades ago, the numbers have ballooned in record time:

The percentage of minors who now identify as transgender has nearly doubled since its last estimate in 2016. Transgender youth has reached about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the U.S., up from 10%.

This sure sounds like the vulnerable “acceding to a demand,” does it not?

According to the study, nearly a fifth of the transgender population is aged 13-17.

The states with the highest proportion of transgender youth were Democrat-led and generally more permissive of classroom instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation.

Dr. Allen Frances, a psychiatrist writing for Psychology Today in 2014, could not have been more blunt about the phenomenon of the weak and vulnerable claiming a trendy medical condition as it applied to the MPD craze:

Multiple personality disorder has always been controversial and contagious. We are lucky that MPD is now in one of its quiescent phases, but it will almost certainly make a comeback before very long. Recurrent false epidemics have occurred several different times during the last century. The trigger is usually either the widespread copy-catting of a popular movie or book, or the fevered preachings of a charismatic MPD guru, or both.

The doctor continues:

Having seen hundreds of patients who claimed to house multiple personalities, I have concluded that the diagnosis is always (or at least almost always) a fake, even though the patients claiming it are usually (but not always) sincere.

In every single instance, I discovered that the alternate personalities had been born under the tutelage of an enthusiastic and naive therapist, or in imitation of a friend, or after seeing a movie, or upon joining a multiples’ chat group—or some combination. It was most commonly a case of a suggestible and gullible therapist and a suggestible and gullible patient influencing each other in the creation of new personalities. None of the purported cases had had a spontaneous onset and none was the least bit convincing.

Dr. Frances sees this as people in genuine pain being manipulated into false solutions:

Why does MPD keep making its periodic comebacks, despite not being a verifiable or clinically useful mental disorder? My best guess is that the labeling of alters offers an appealing and dramatic metaphor, an idiom of distress. Under the influence, pressure, guidance, and modeling of external authority, suggestible individuals find in MPD a convenient way to describe, explain, and express their conflicting feelings and thoughts. But the metaphor often takes on a dangerous and impairing life of its own, feels all too real to the patient, and contributes to regression, invalidism, and a negative treatment response. And many who present with MPD have a real and treatable psychiatric disorder that is masked by it.

If this “appealing metaphor” is now presenting itself as “gender dysphoria” today, and the evidence is all around us that it is, what does this say about the state of our warped and deeply corrupt medical establishment?

About . . . . Intelligence . . . . Membership