Americans have always liked to think that one of the remarkable achievements of U.S. society — differentiating it from the Old Country — was our social mobility. Our “aristocrats,” whether moneyed or “stars,” were mostly only a generation away from obscurity. And chances were their progeny wouldn’t hang on to their status unless they, too, were high achievers.

That belief in American meritocracy has been challenged by recent studies. Statistics seem to indicate greater disparities are being passed on from generation to generation, despite abundant examples to prove the old claims. There are, after all, all those new Silicon Valley millionaires. And Virginia, the largest slaveholding state, has already elected, in 1989, the grandson of a slave as governor, the first black governor since Reconstruction.

Mitt Romney’s recently largely misinterpreted remarks — he whimsically said that, given his pledge to reduce federal income taxes, he hadn’t much chance attracting support from the 47 percent of voters not paying any — transmogrified into the usual campaign cackle. The essential questions — whether American society has become less entrepreneurial, more dependent on government handouts and regulation, less competitive and vibrant — were lost in the volley.

Not that the argument isn’t complicated. Our revolutionary technology alone has changed the world in so many ways. My mechanic points out he now must have several dozen computer software programs — no longer just wrenches and sweat — to keep my two-decades-old crate going. When I tracked down an appliance repairman to fix our dryer recently, the initial telephone “interview” involved a dozen questions I couldn’t answer.

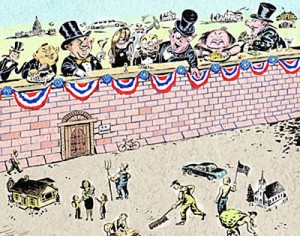

But economics and changing technology are not by any means the whole story. What some of us sense is a growing division in American life between a self-appointed, supposed meritocratic elite and the rest of us plebes. And just as in the last days of the Roman Republic, we, like the Roman plebeians and the nouveau riche entrepreneurs, feel threatened.

Has American society increasingly come under the thumb of a well-heeled, educated (after a fashion), ultra-urbanized cultural leadership that thinks it knows what is good for the rest of us, whether we like it or not? In so many ways, Obamacare was the apotheosis of that phenomenon. And, alas, in addition to failing to solve the fundamental problem of rising medical costs, the early returns on Obamacare indicate that the anointed hadn’t a clue what they were really putting together.

In the communications arts, more than a decade ago, the brilliant social thinker — if rather lousy politician — Daniel Patrick Moynihan signaled what had happened to the capital’s press corps. Mr. Moynihan was responding to the mau-mauing he had taken for an insightful inquiry into the black underclass. But in an aside, he suggested there had been no fruitful discussion, in part because of the changed nature of newspapering: In the course of one generation, he claimed, the press had gone from being populated by working-class stiffs trying to get their street smarts past editors and publishers to pseudo-intellectual suburban dilettantes convinced they had to lead, to tell readers what they should think.

As print media dies in the cataclysm of the digital revolution, Mr. Moynihan’s forebodings are exemplified in a New York Times no longer “the newspaper of record,” but an outrageously polemical, irascible, ideologically challenged schoolmarm. Then there’s its politically correct twin, Washington-subsidized NPR and PBS, in obvious violation of the First Amendment’s prohibition against government interference with the press.

Free and universal public school education, which was once America’s unique contribution to Western culture, now consists of holding pens no longer able to teach literacy. Ignoring history’s examples of successful education under a tree and in one-room schoolhouses, all emphasis has been placed on skyrocketing expenditures. The recent Chicago impasse is the scandalous product: teachers unions demanding compensation at double their students’ parental income and refusing basic measures of job performance.

Tertiary education, too, for all its vaunted reputation, has become an anachronism, with costs far exceeding inflation in other sectors. Full professorships paying $200,000 a year, with magnificent perks, are one part of the problem. Nor does it occur to our “tenuratti” to question whether benefits-lined guaranteed lifetime employment is either tenable or fair. No wonder the essence of the university — a wide, free exchange of competing ideas — is often outrageously violated in an environment that perhaps more than any other encourages conformity to “politically correct” nostrums.

Sol W. Sanders, ([email protected]), writes the ‘Follow the Money’ column for The Washington Times on the convergence of international politics, business and economics. He is also a contributing editor for WorldTribune.com and East-Asia-Intel.com.