Special to WorldTribune.com

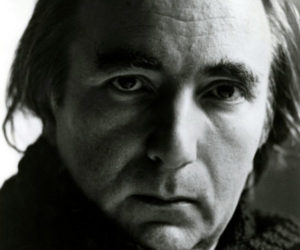

Longtime WorldTribune.com and New York Tribune columnist Lev Navrozov died in New York on Jan. 22, his son said.

” The Orthodox priest who came to the hospice to administer the last rites could not do so, as one must repent one’s sins and the dying man was unconscious, but truth to tell, my father had no sins to confess,” Andrei Navrozov wrote to his father’s friends and admirers. He went on to explain that Lev Navrozov had “lived his whole life in a … cell of the mind, as close to monastic confinement as the profane world has to offer.”

WorldTribune editor Robert Morton called Navrozov “a formidable intellect who sacrificed the last half of his life in a valiant and unrelenting effort to awaken American minds to harsh realities outside the geopolitically sheltered United States.”

Navrozov was born to playwright Andrei Navrozov (after whom his son was named), a founding member of the Soviet Writers’ Union, who volunteered in World War II and was killed in action in 1941.

After studying at Moscow Power Engineering Institute, he transferred to the exclusive Referent Faculty of the Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages, a faculty created by Joseph Stalin’s personal order to produce a new generation of experts with a superior knowledge of Western languages and cultures.

Writes his son Andrei, “this was a man who, while a university student in Moscow, secretly studied forensic science to ensure that his vote against the Communist Party in the 1950 “election” — quite probably, the only such protest vote in the whole of the Stalin era — would not be traced to him through the handwritten bulletin.”

On graduation in 1953, he was offered a “promising position” at the Soviet Embassy in London, with the attendant obligation to join the Communist Party. He declined both offers, and refused all government posts or academic affiliations as a matter of principle. Regarded as a unique expert on the English-speaking countries, he worked exclusively on a freelance basis.

Navrozov was the first, and to date the last, inhabitant of Russia to translate for publication works of literature from his native tongue into a foreign language, including those by Dostoevsky, Hertzen and Prishvin, as well as philosophy and fundamental science in 72 fields. In 1965, still freelance but now exploiting what amounted to his virtual monopoly over English translations for publication, Navrozov acquired a country house in Vnukovo, sixteen miles from Moscow, in a privileged settlement where such Soviet elites as Andrei Gromyko, then Foreign Minister, and former Politburo member Panteleimon Ponomarenko had their country houses.

In 1953 he began his clandestine documented study of the history of the Soviet regime, working on a cycle of books in the hope of smuggling the manuscript abroad. During this period he published translations only, publishing no original work in view of the unacceptable limits imposed by censorship. In 1972 he emigrated to the United States with wife and son, after receiving a special invitation from the U.S. State Department arranged through the intercession of several politically influential American friends.

From 1972 to 1980 he contributed to Commentary magazine, including the 1978 publication of the bitingly critical articles “What the CIA Knows About Russia,” which Admiral Stansfield Turner publicly admitted he was unable to rebut.

In 1975, Harper & Row published the first volume of his study of the Soviet regime from within, The Education of Lev Navrozov. The book recounts the contemporary effects of Joseph Stalin’s public relations campaign in the aftermath of the assassination of rival Sergei Kirov. “It bids fair to take its place beside the works of Laurence Sterne and Henry Adams,” wrote the American philosopher Sidney Hook,”… but it is far richer in scope and more gripping in content.” Robert Massie, author of Nicholas and Alexandra, wrote of the author’s “individual genius.”

Saul Bellow, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, responded to “The Education” by using Navrozov as the model for a modern Russian dissident thinker in two of his books, thereby beginning a lively correspondence that continued until the American novelist’s death. In particular, the narrator of More Die of Heartbreak describes Navrozov, along with Sinyavsky, Vladimir Maximov and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, as one of his epoch’s “commanding figures” and “men of genius.”

After 1975, Navrozov published several thousand magazine articles and newspaper columns for the New York Tribune (later re-named the New York City Tribune), Newsmax and World Tribune which, however diverse the subjects drawing his attention and commentary, have a common theme, namely the incapacity of the West to survive in the present era of increasingly sophisticated totalitarianism.

He also served as honorary chairman of the “Alternative to the New York Times Committee” during the early 1980s and generated intense interest in the Soviet emigre community when he challenged an editor of the Times to a public debate at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. The editor did not appear and Navrozov addressed the audience on the need for a competing serious international newspaper in New York to refute the outsized influence of the N.Y. Times.

“Lev had the humility of a young child but was utterly incapable of compromising his integrity,” Morton said.

“He could be fun, describing as the ‘Siberian Jew syndrome’ as the tendency of conservatives to despise other conservatives with extra vehemence. And he despaired of ever reaching Americans who were obsessed, he said, with ‘fun, fun, fun!’ ”

Jewish by birth, Navrozov panicked during immigration in New York when spotting the space on the form after ‘Religion’. Not wanting to be on the next flight back to the USSR, he said he responded after much hesitation: “personal mysticism.” Near the end of his life, he requested baptism as a Christian, friends said.

Lev Navrozov was the founder, in 1979, of the Center for the Survival of Western Democracies, a non-profit educational organization whose original Advisory Board brought together Saul Bellow, Malcolm Muggeridge, Dr. Edward Teller, Lt. Gen. Daniel O. Graham, the Hon. Clare Boothe Luce, Mihajlo Mihajlov, Sen. Jesse Helms, and Eugène Ionesco.