Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk

By Donald Kirk

SEOUL — The U.S. is pursuing a careful policy of appearing to support South Korea’s drive for reconciliation and dialogue with the North but holding out the option of refusing to go along with anything short of complete certainty that Kim Jong-Un is dismantling his nuclear program

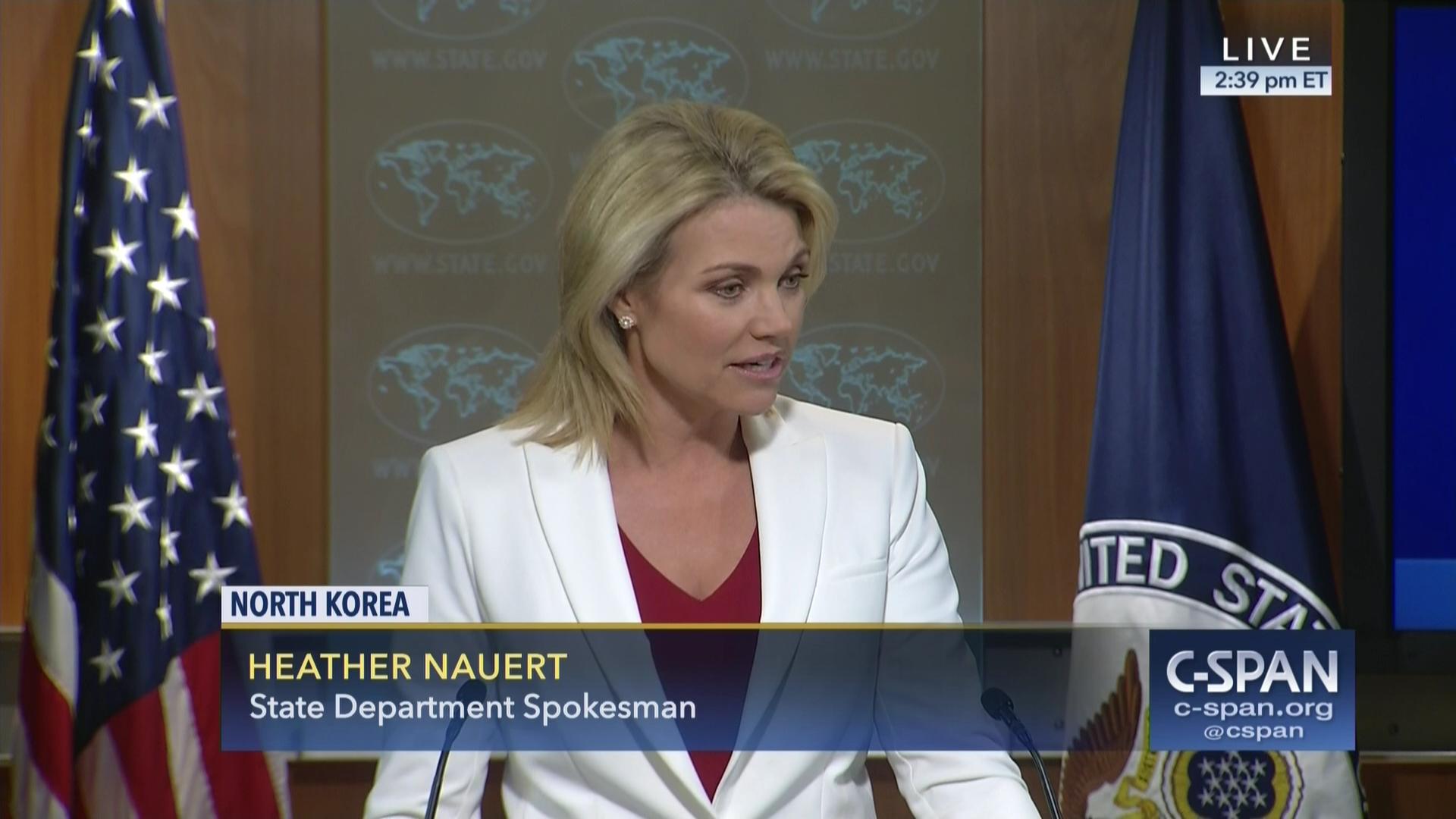

The carefully scripted U.S. strategy is evident in the measured words of American diplomats, notably Heather Nauert of the State Department, who said the U.S. would indeed like “a formal end to the armistice” that stopped the Korean War 65 years ago. That remark reflects the fact that an armistice or truce is not the same as a treaty – and that technically the war is still going on.

The Americans, however, are not actually saying they would support a peace treaty especially since the newly installed national security adviser, John Bolton, has specifically said he opposes a treaty. Bolton clearly views the North’s demands for a treaty as a ruse intended simply to get the American troops to leave Korea, exposing the South to attack as Kim Jong-Un’s grandfather, Kim Il-Sung ordered in June 1950.

Bolton has no doubt been pressing President Trump to persist in hedging on whether he will fall for any deal that Kim might try to get him to accept, and Trump is saying he won’t even agree to talk to Kim at all if it’s not clear that he will seriously discuss abandoning his nuclear program. In fact, Trump is raising the possibility of his meeting with Kim ending in its disruption in which he would simply walk out of the room if it became clear that Kim was talking nonsense and had no intention of giving up anything.

The Americans, though, are anxious not to offend Moon by appearing not to applaud his efforts at reaching a deal with Kim Jong-Un. Obviously it won’t be known until after the Moon-Kim summit if Kim is misleading the world by pretending to want to reach an accommodation on his nukes. Trump’s position is that of wait-and-see – waiting to see what happens.

It was in that spirit that Heather Nauert at the State Department said that a “formal end” to the Korean War would be “something that we would support” – the kind of remark that could be interpreted in different ways depending on circumstances. The fact that she avoided use of the words “peace treaty” revealed the questions raised by a term that would as be open to interpretation and controversy.

Foes of a peace treaty believe the document would lead to charges and counter-charges of “violations” while still not resolving overwhelming problems surrounding the confrontation of forces on the Korean peninsula. Worse yet, the final result could be anything but peace – rather, a second Korean War in which North Korea staged incursions and then an invasion of the South and the peace treaty proved not be worth the paper it was printed on.

Nonetheless, Trump is definitely going along with the upbeat talk. One hopeful sign is North Korea may well release three American citizens, all Korean-American, who have been held for no reason by North Korean authorities.

The three, Kim Hak-Song, Kim Dong-Chul and Tony Kim, all face charges simply of “hostile acts” with no clue as to what they did. Their release depends on the mood of Kim Jong-Un, who is expected to see it as a way to win over skeptics in the U.S. and gain support for whatever document he proposes.

Among those who see the release of the three as a strong possibility is Bill Richardson, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and former governor of New Mexico. Richardson, who has made a number of visits to North Korea, said their release would show North Korea’s interest in accommodating other demands, including renewing the deal under which U.S. teams have scoured battle scenes in North Korea in search of remains of American soldiers listed as missing in the Korean War.

Trump has signaled the significance of the release of the three by saying he believes “there’s a good chance” they will all be sent home, possibly before he even it down with Kim Jong-un to talk about the overwhelming issue of North Korea’s nukes.

Despite doubts about whether the Moon-Kim summit will really lead to anything, or whether Trump can possibly come to terms with Kim, the mood here is overwhelmingly hopeful. As in Seoul, the sense among analysts and observers of all that’s been happening on the Korean peninsula in recent years is that peace, if not a peace treaty as such, is definitely in the air. Trump, they believe, would be in no position suddenly to reverse course and walk out of a meeting with Kim.

A game-changer has been CIA Director Mike Pompeo’s secret mission to Pyongyang in which he actually met Kim. He came back saying they had had “a good meeting,” talking over what will be discussed at the summit.

But wait! So far we don’t even know when or where the Trump-Kim summit would happen. At first we heard “in May,” and now the thinking is in June. As for where, we’ve heard everything from Pyongyang to Panmunjom to Ulan Bator to the island of Jeju, South Korea.

Bill Richardson said Trump and Kim could even meet in Russia, maybe Vladivostok, a train ride away from Russia’s brief border with North Korea along the Tumen River. More realistically, Richardson mentioned Geneva.

That would make sense since Kim went to school near there in Switzerland and numerous talks on North Korea have gone on in Geneva. The U.S. and North Korea in October 1994 agreed on the “framework” under which North Korea suspended its nuclear program and shut down its five-megawatt plutonium reactor at Yongbyon. That deal that ended abruptly in 2002 after the revelation that the North also had a secret program for developing nuclear warheads made of highly enriched uranium.