Special to WorldTribune.com

By Gregory R. Copley, Editor, GIS/Defense & Foreign Affairs

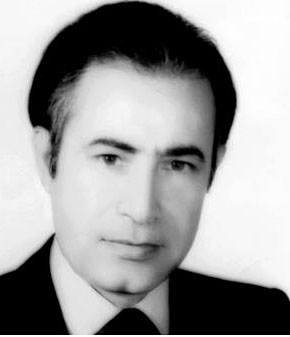

[Editors’ Note: Dr. Assad Homayoun, former Minister for Political Affairs at the Iran embassy in Washington, was an early WorldTribune.com Advisory Board Member and Contributing Editor. A passionately pro-U.S. patriot of Iran, he provided expert analysis and information on developments in Iran both through his own writing and that of other writers with whom he collaborated. The concluding paragraph of one such article best summarized his core conviction and prayer for his homeland.]Assad Homayoun had one burning, unfulfilled wish when he died after a long illness in Washington, DC, on April 11, 2020, a few weeks after the Now Ruz holiday marked the start of Spring.

He wished Iran to be free.

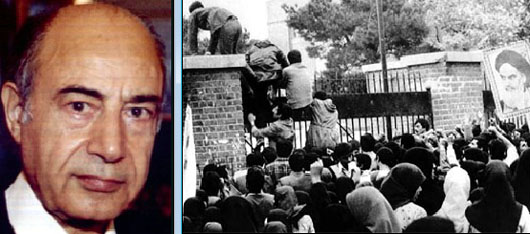

Assad had devoted his life to that end since being trapped in exile in the U.S. from early 1979, his world dislocated as the ailing Shah Reza Pahlavi was pushed from his country.

Iran’s friends had abandoned their old ally. It was to be the world’s loss as well. But Assad Homayoun’s life in exile was far from wasted. He kept alive the flame of Iran’s Persian heritage and was an inspiration to Iranians inside the country and in the diaspora. He was one of the greatest repositories of strategic philosophy and knowledge in the world. His reading and understanding of strategy was rare and encyclopedic. So he became Iran’s gift to the world and therefore one of Iran’s greatest losses.

If the revolutionary clerics could not listen to him, then neither could they listen to reason; nor could they be trusted to have the good of Iran in their hearts and minds.

Assad would have been 88 years old in July 2020. He was born in Iran in 1932, and became a diplomat, serving with distinction in Pakistan, the U.S., and elsewhere. The collapse of Iran in early 1979 — it was a chaotic vacuum into which “Ayatollah” Ruhollah Khomeini stepped when the Shah voluntarily went into exile; there was no revolution — meant that he was forced to turn from advising his Government to teaching the world at large. He immediately became associated with the International Strategic Studies Association (ISSA) and Defense & Foreign Affairs publications.

He created, with Gen. Bahram Aryana, the Azadegan Foundation to help create a free and democratic Iran, and to sustain teaching of Persian history, values, and literature.

His time as a diplomat in Washington, DC, enabled him to complete his doctorate at George Washington University, and, with the collapse of the Shah’s Government and nowhere to go, he taught international relations there.

He was perfect for that assignment; he understood the world, and history, as few do.

His students loved him. I met him well before that, however. In 1974.

He had read something I had written and flew from Washington to San Francisco to meet with me. We had more meetings like that before Defense & Foreign Affairs and ISSA moved to Washington, DC. The photograph of him above was one he gave me at that time — it was not an uncommon practice in those days to exchange photographs with friends — and it has lived ever since on the bookshelves beside my various desks (in San Francisco, London, and Washington).

Assad wrote regularly for Defense & Foreign Affairs, and was a founding member of the International Strategic Studies Association’s prestigious College of Fellows. He broadcast regularly into Iran, and thus helped keep alive the spirits of those who yearned for the restoration of Persia’s dignity and freedom.

Flying over Iran almost 23 years to the day before he passed away, I looked down upon the Alborz Mountains. He had been in exile then for almost two decades, and it had taken its toll on him. So there, gazing down at the snow, I wrote the verse which appears below.

The transformation of Iran and the loss of his diplomatic posting eventually cost Assad his marriage, but his son, Aresh, was a constant inspiration during his four subsequent monastic decades of reading and writing in exile.

Assad Homayoun changed my approach to life, not only by patiently working with me to create new approaches to strategy, but also by presenting the world through the great humanistic and poetic lenses of the great poets: Omar Khayyám, Ferdowsi, Hafez, Saadi …

He discussed Persian carpets and strategy with my other mentor, Stefan Possony; he took my wife to his heart, along with my entire family.

He was patient, kind, and very wise. And he was a patriot who ached always for his homeland.

Assad was one of my greatest teachers. But he was also my dearest friend, brother, and colleague.

No words are enough.

To an Exiled Patriot, Too Long from Home

It is April, yet there remains

Snow, dappled on the

foothills of the Alborz range,

Leeched from the perpetually

Crisp and clouded summits

of a silent, ageless place.

And there, for now, the winds

are hushed; few souls venture,

Yet clear before, I see translucent,

shimmering, your face.

Winter goes, yet there remains

Ice, hard beneath the

drumhead of the Persian plains.

And here, for now, the winds

resound; Ferdowsi sleeps,

While in the absence of your soul, I weep.

— Above Iran: Karachi-London flight, April 15, 1997