Special to WorldTribune, March 24, 2021

Analysis by Eric Clary

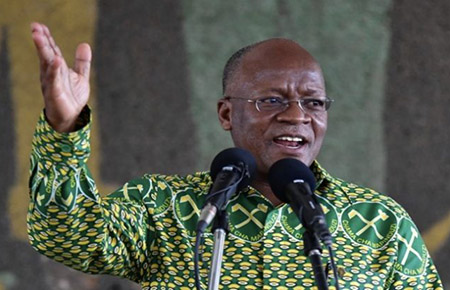

Tanzania’s former Populist President John Magufuli’s state funeral commenced on March 22 before throngs of supporters. The coronavirus lockdown critic made international headlines in May of 2020 when he made light of a popular COVID testing kit.

Magufuli, a PhD chemist, embarrassed the medical establishment when he announced that a pawpaw and goat had tested positive for COVID-19 according to the kits.

When the government confirmed that Magufuli had died of heart disease on March 17, the corporate media focused on unconfirmed reports the lockdown skeptic had succumbed to COVID, a twist in irony that seemed too good to be true. But, for some, the media’s selective reporting has raised more questions than they answered.

Magufuli is somewhat a giant in Tanzania. The social conservative and traditional Catholic proved a formidable roadblock to globalists.

Upon entering office, he implemented commonsense austerity reforms that quickly made him enemies. Among the measures were limits on foreign travel which he applied to himself. In 2018, Magufuli raised eyebrows when he declined to attend the United Nations General Assembly summit in New York in order to save money.

He also downsized the presidential cabinet, imposed restrictions on government officials’ foreign travel and removed ‘ghost workers’ from the state’s payroll.

However, the enemies that Magufuli made domestically paled in comparison to those from abroad.

In a blatant attempt to intervene in domestic policy, globalist institutions, in what could only be described as quid pro quo, withheld finances from Dar es Salaam when Magufuli enforced Tanzania’s longstanding anti-homosexual laws.

According to Time, “The World Bank withdrew a $300 million loan to Tanzania [in November 2018], in response to a number of controversial laws passed by the national legislature in recent months. As well as clamping down on an existing ban preventing pregnant girls from attending school, Tanzania has made it illegal to question official statistics and cracked down on LGBT rights in a country where homosexuality is already illegal.”

The United States followed suit in 2020 by imposing a travel ban on Tanzania and sanctioning regional commissioner Paul Christian Makonda for “targeting marginalized individuals.”

The State Department’s timing was a blatant attempt to inflict maximum damage on Magufuli’s October election bid. Most leaders in Magufuli’s position would have caved, but the president’s tango with western powers only prepared him for what came next.

In April of 2020, Magufili rejcted a Chinese debt trap initiated by his predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete. The “deal”, according to the International Business Times, was for “Chinese investors to build the port on condition that they will get 30 years to guarantee on the loan and 99 years uninterrupted lease, according to local media reports.”

The unfavorable deal was renegotiated but then dropped by Beijing. The move strengthened the African leader’s populist bona fides and testified to Tanzania’s trend towards self-reliance.

Magufuli’s toughness paid off. On July 1, 2020, The World Bank raised Tanzania’s economic status to the lower-middle income category, a sizable jump for Tanzania and the region. But the international community was not without resentment.

When The New York Times ran a deceptive article entitled, “John Magufuli, Tanzania Leader Who Played Down Covid, Dies at 61,” the obvious takeaway was that the former president died of COVID-19. Yet nowhere in the article does Times reporter Abdi Latif Dahir confirm that Magufili had tested positive for coronavirus.

Nevertheless, the “Magufuli died of Coronavirus” narrative was parroted by all the major international media outlets. As convenient of an explanation as that may sound, the question not being addressed is how a major African leader succumbed to coronavirus on a continent with a lower COVID mortality rate than the United States.

Such improbabilities also apply to other African leaders who, like Magufuli, bucked international “norms” on policy issues out of synch with the values of average folks. The challenges they shared will be addressed in an upcoming article.