Two recent deeply intertwined violent events demonstrate the terrible burden hanging on the outcome of U.S. intervention in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

An American soldier’s rampage allegedly taking the lives of 17 Afghan villagers paralleled the attack of a Franco-Mahgrebian youth resulting in seven deaths of French [Muslim] veterans and Jewish civilians. Not for a moment should any attempt be made to equate them — or, indeed, to make any moral comparative judgments. One episode was apparently a breakdown into temporary insanity; the other was — however equally deranged — a premeditated attempt at political assassination.

But they are linked.

The murders by Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, on his fourth tour in a Mideast war zone, seems a likely symptom of the increasingly heavy burden he and his American warriors have had to shoulder. But if his murderous outburst could be rationalized as inevitable in no-front-lines guerrilla warfare, seemingly stalemated, it also highlighted the American public’s growing fatigue with a decade of involvement in “faraway countries about which we know little”. Only the valor and sacrifice of a small portion of the U.S. population willing to commit to professional military service has made this effort possible — a far cry from echoes of the skewed draft army involved in the Vietnam retreat.

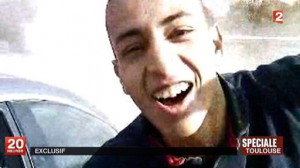

Mohammed Merah, whom, ironically, a journalist interlocutor before the killings characterized as speaking impeccable French, is one of thousands of young Muslims, often second and third generation reared in the West, who after becoming radicalized for whatever social reasons, go to the Mideast for guerrilla training to fight for Islamicist causes. Some return and melt back into the assimilated population. But others, unpredictably even if suspects known to authorities as in Merah’s case, silently dedicate themselves to “lone wolf” terrorism. Three decades of war in Afghanistan already has provided fertile ground for their apprenticeship. But Pakistan’s growing Islamicist radicalism suggests possibilities for a much larger new generation of terrorists among that country’s vast diaspora in the West.

U.S. and NATO intervention in the region after 9/11 — however differently it might now appear — was logical in eliminating an important terrorist safe haven from where new strikes could have originated.

With 20-20 hindsight, attempting to modernize an isolated, pre-industrial Afghanistan society might be viewed as a bridge too far, rather than choosing a simpler strategy of destroying the terrorists’ nest, ousting the regime that gave it sanctuary, and abruptly withdrawing. That larger Afghanistan effort and again picking up an earlier abandoned enormous aid commitment for a near-failed Pakistan state has turned out far more costly in blood and treasure than anticipated by most Americans unacquainted with the region.

Now mesmerized by its own continued economic problems and the four-year cycle to choose leadership, the U.S. flirts with a precipitous withdrawal from Afghanistan, and, inevitably as a result, from Pakistan. The arbitrary troop stand-down already scheduled by the Obama administration already has emboldened old enemies. Without a definitive U.S. victory, Taliban remnants shading off into the kind of terrorists who made 9/11 are brazenly emerging, not only there, but elsewhere throughout the Muslim world.

That a U.S. withdrawal would return the region to the status quo ante seems unlikely. Far too much has happened. But continued targeting by U.S. drones [with Pakistan’s tacit intelligence collaboration] of “foreigners” in the tribal regions along the fictitious Afghanistan-Pakistan border is evidence enough to be concerned about the effects of a rapid U.S. retreat.

But it may well be the U.S. public will make that choice for all the obvious reasons.

As always there is no predicting unanticipated consequences. But a likely possibility is chaos in Afghanistan itself, and further erosion of a Pakistan regime under its current incompetent civilian leadership and an increasingly discredited military [on which the regime has so heavily depended since independence]. A Pakistan implosion — so closely linked to Afghanistan events — would mean its 200 million people would become an even more fertile breeding ground for terrorists. Furthermore, its neighbor India — with an even larger affiliated Muslim population — would not be able to stabilize its western frontier. In fact, Pakistan ethnic and regional disintegration would be a threat to Indian unity.

That is only part of the still incalculable price for precipitous U.S. withdrawal, countering all those very good arguments for it with the American public and those now running for high office.

Sol W. Sanders, (solsanders@cox.net), writes the ‘Follow the Money’ column for The Washington Times on the convergence of international politics, business and economics. He is also a contributing editor for WorldTribune.com and East-Asia-Intel.com.