Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk, East-Asia-Intel.com

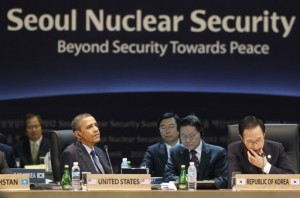

SEOUL — President Barack Obama’s oratorical flights against North Korea’s plan to fire a long-range rocket next month may have pleased his South Korean hosts, but evoked little more than polite responses from the Chinese and Russians who exercise the most influence in Pyongyang.

The failure of Team America so far to get anywhere in dissuading North Korea from popping off the rocket-cum-satellite was particularly galling after all the one-on-one meetings between Obama and many of the more than 50 heads of state at this week’s portentously named “nuclear security summit” in Seoul.

The final insult was North Korea’s quick and firm rejection, in the final hours of the summit, of Obama’s plea to drop the shot.

A North Korean Foreign Ministry spokesman, in a lengthy defense of North Korea’s determination to go through with the launch, stressed the goal was to put a satellite into orbit. North Korea “will not give up the satellite launch for peaceful purposes,” the spokesman was quoted as saying. This was “a legitimate right of a sovereign state” and was “essential for economic development.”

The emphasis on economic development appeared a rebuff not only of Obama but also of China’s President Hu Jintao and Russia’s outgoing President Dmitry Medvedev.

Both of them, in talks with Obama on the sidelines of the two-day summit, agreed it would indeed be good if the North would cancel the plan for the missile test and honor the “moratorium” that the U.S. believed was achieved in talks between U.S. and North Korean envoys on Feb. 29. Clearly, they did not have a rocket launch in mind when they urged the North to focus instead on development.

Chinese and Russian expressions of “concern” even a reported denunciation from Medvedev of the North Korean plan, fell short of a commitment to do much about it. “China is certainly talking politely,” said Han Sung-Joo, a former foreign minister and ambassador to Washington, “but I don’t think China will actually do that” — that is, risk upsetting the North Koreans by withholding some of the fuel and with which it keeps its North Korean protectorate alive.

“China and Russia will put some modest pressure [on the North],” said Paik Han-Soon, director of the Center for North Korean Studies at the Sejong Institute, a leading think-tank in Seoul. “But they will not be taking concrete steps.” They know very well, he said, that “North Korea will go its own way” regardless of what anyone says.

Instead, Han forecast “China will try to persuade South Korea to make it to six-party talks” on North Korea’s nuclear program. The talks, hosted by China, including the U.S., Japan, Russia and the two Koreas, were last held in Beijing in December 2008 — and are still regarded as essential in bringing about rapprochement on the Korean Peninsula.

The worst irony is the abiding sense that North Korea can actually get away with firing the rocket, despite all protests, on the calculated gamble that the U.S.’s rhetoric will fail to gain significant traction in the run-up to the U.S. presidential election in November and South Korea’s election in November.

“North Korea has given a kind of dilemma to both the U.S. and South Korea in that they will go ahead with the rocket launch,” Han surmised.

If the U.S. “breaks off the February 29 agreement” and cancels its commitment to provide 240,000 tons of emergency food aid, he said, the Americans “reduce the opportunity” for inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency to visit the North Korean nuclear complex at Yongbyon as also agreed.

“North Korea can then put all the blame on the U.S.,” Han reasoned, “and the U.S. will have to find a way to punish North Korea”. That, he said, “is difficult” in view of the Chinese and Russian positions.

By the time the whole show wound down, the summiteers could agree on a declaration against all forms of nuclear terrorism that said not a word about the issues that are dominating the entire gathering, the nuclear programs of North Korea and Iran.

In fact, the stated purpose of the summit was to come up with ways to combat nuclear terrorism — especially the danger of highly enriched uranium falling into the hands of terrorists — but avoid censuring individual countries or programs. A long-winded final communique reaffirming “our shared goals of nuclear disarmament, nuclear nonproliferation and peaceful uses of nuclear energy” made plain that compliance was voluntary.

Perhaps the most substantive accomplishment was an understanding on coordination on reducing the amount of highly enriched uranium used for medical purposes. “We are working very aggressively,” said U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu, “so terrorists who might have access to this material cannot have access.”

For all the talk, the sense persists that North Korea will return to a talking mode and get the U.S. to make good on the bargain after celebrations marking the centennial on April 15 of the birth of founding leader Kim Il-Sung, grandfather of the young new leader, Kim Jong-Un. North Korea has said it will fire the rocket at around that time.

“North Korea is not interested in what was discussed and achieved here,” said Paik. “They cannot expect anything good to come out of this summit.”

Obama, however, glossed over the potential pitfalls as he talked to students and faculty members at Hankook University of Foreign Studies before getting down to serious diplomacy.

In a special touch of drama, he remarked, “Here in Korea, I want to speak directly to the leadership in Pyongyang.” The U.S., he said, “has no hostile intent toward your country”, is “committed to peace” and “prepared to take steps to improve relations” — the reason, he said, “we have offered nutritional aid to North Korean mothers and children.”

Dangling food aid like a bait, he advised the North Koreans, “Know this — there will be no more rewards for provocations.” In other words, you can forget the food if you fire that rocket.

For all the talk, the sense persists that North Korea, after the hullabaloo over the rocket has died down, will return to a talking mode and get the U.S. to make good on the bargain. “Washington needs to manage the situation so they don’t completely destroy the formal talks,” said Choi Jin-Wook, a senior researcher who specializes on North Korea at the Korea Institute of National Unification. “They will still need to get North Korea involved in that dialogue.”

Nor was North Korea the only more or less intractable problem on the agenda — that is, the agenda of talks-on-the-sidelines, not the formal nuclear security summit.

Obama was also anxious to get across the urgency of persuading Iran to cease and desist from developing its own nuclear warheads — if indeed it is. “There is time to solve this diplomatically, but time is short,” he said. “Iran’s leaders must understand that there is no escaping the choice before it.”

The topic of Iran, he promised, would also come up in his talks with Chinese and Russian leaders, but here too he was not believed to have elicited more than polite responses, possibly qualified agreement but no real commitments.

Obama’s talks with Medvedev were particularly dicey since Vladimir Putin, emerging from a hiatus as prime minister, will take over again as president on May 9.

He promised at Hankook University to discuss the whole issue of “reducing not only strategic nuclear warheads but also tactical weapons and warheads” when he meets “president Putin” in May. Sensitive to Putin’s objections to North Atlantic Treaty Organization missiles pointed toward Russia, he said missile defense “should be an area of cooperation, not tension.”

That sentiment, however, led to the biggest flub of the summit — remarks that Obama made to Medvedev when he thought the microphones were turned off. He would, he said, have “more flexibility” on missile defense after the presidential election in November.

“This is my last election,” he reminded Medvedev, meaning he would then be free to wheel and deal. The line, “my last election” was perfect for a host of enemies campaigning to make sure the election will be just that — the last chance he’ll get on the American political stage.