Special to WorldTribune.com

Analysis by GIS/Defense & Foreign Affairs, Pretoria

To witness South Africa’s descent into chaos is like experiencing a powerless, slow-motion dream sequence.

There is a widespread consensus that President Cyril Ramaphosa has lost support inside and outside the governing African National Congress (ANC), and the ANC has become so distrusted that it could not win the next election.

But that may be a moot point, in any event, as the COVID-19 lockdown of the country polarized much of South African society to the point of no return. A lot of it was avoidable.

The government in May 2020 continued its ban on the sale of cigarettes and alcohol as part of the COVID-19 measures, and when the president overruled some of the tobacco measures, he was countermanded and made to look weak.

The ban on these consumables mostly affected poorer African segments of society where there is already seething discontent and fear, fueled by rising unemployment. Moreover, it also hit a significant area of government revenue- generation. Legal maneuvers mean that the ban on tobacco sales would soon be lifted, but much damage was done to the credibility of the Government.

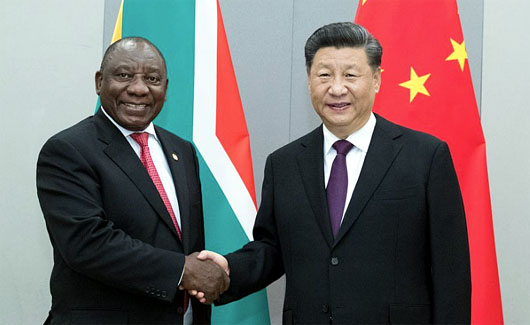

And President Ramaphosa now has nowhere to go to help fund a bankrupt economy. His biggest ally, the People’s Republic of China, seems unlikely to be able to help, and, anyway, it knows that any additional funding or investment would only be siphoned off — as has already happened — to ANC leaders.

And the ANC would resist allowing Ramaphosa to go to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would demand a restructuring of the financial system to show greater transparency and accountability.

The result is that the COVID-19 lockdown may be the only thing which could save Pres. Ramaphosa and the ANC. It is already being discussed in South Africa as a de facto coup d’etat. The question, however, is “what’s next?” It’s hardly a matter of “getting the economy moving again”. What economy? ANC corruption had destroyed the economy before the COVID shutdown.

In early May 2020, yet another parastatal, the Passenger Rail Authority of South Africa (PRASA), joined the list of “hopeless basket cases”, which included South African Air-ways, and the electricity supplier. PRASA, which was already insolvent in January 2020, subsequently lost another 199-million rand ($10.83-million) of income thanks to the lock- down and now has a projected loss for the year of R757-million ($41.19-million). In addition, rail services, already suffering, were now in an even worse state. The national network suffers from decades of mismanagement, neglect, and ethnic cleansing, while Cape Town’s local but PRASA-owned Metrorail system had stopped running altogether by May 2020, to the detriment of uncounted thousands of daily commuters from outlying and mainly less well-off areas.

Noted South African journalist Jeremy Gordin — who wrote the 2008 book, Zuma: A Biography, on former President Jacob Zuma — noted on May 7, 2020:

Is the Government — President Cyril Ramaphosa, his cabinet, the National Command Council and perhaps the ANC too — dealing as best as they can with the local manifestation of COVID-19, or are Ramaphosa et al using the national crisis for more nefarious purposes?

The ‘events’ that have precipitated the second part of the question include, among other things, debates about whether a lockdown was the correct strategy — whether it was applied at the right time and/or using the correct parameters; the martial law type deployment of the SANDF [South African National Defence Force]; and foolish and inept elements of the lockdown.

Gordon noted: “If Ramaphosa controlled a large majority within the ANC’s top echelon, he could have done what he wanted to do. But, as noted, he’s not even allowed to let people have a smoke.” He concluded by noting that unless some easing of the lockdown occurred soon, there would be no South African economy left to save.

Widespread suffering, to an even greater extent than now, would likely follow any protracted lockdown. Frustrations, particularly fueled by the denial of the small pleasures of tobacco and alcohol in the townships, would quickly return widespread violence to the streets, and the two relatively stable parts of the country — KwaZula-Natal in the East, and the Western Cape — would almost certainly reinforce their inclination toward a more formal secession from the Republic of South Africa.

Defense & Foreign Affairs asked in a Sept. 19, 2019, report: “How Long Can South Africa Survive as a Cohesive State?”, noting: “The Zulu King, Goodwill Zwelithini, has extensive, real political rights over KwaZulu-Natal. In November 2017, the ANC Government in Pretoria threatened to seize the Ingonyama Trust, the owner of about 60 percent of the land in KwaZulu-Natal, which has always historically been part of the Zulu Kingdom. King Goodwill said then: ‘We must not be provoked. There is no need for the Zulus to be abused by their Treasury, because that will force me — and the world will agree with me — when I declare that I want me and my nation to live on our own and develop on our own, because in South Africa development is selective.’”

“The King subsequently offered protection to Afrikaaner farmers threatened by the ANC with ‘expropriation [of their land] without compensation’, saying that they would come under his protection in KwaZulu-Natal, on the Eastern littoral of the Cape of Good Hope. The King also had offered to return those areas of the former Natal which were taken by the British from Eswatini, and, indeed, an independent KwaZulu would almost certainly ally itself with already-independent Eswatini.”

But for now, there is no let-up in the downward slide of South Africa.