Special to WorldTribune.com

By Golnaz Esfandiari, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

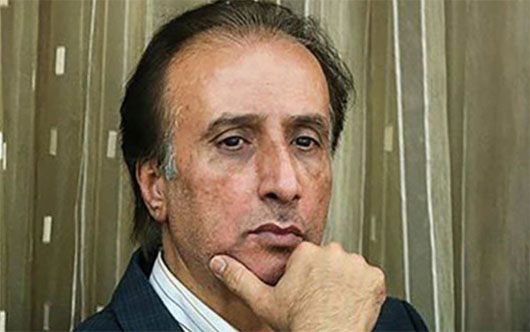

Mohammad Reza Hayati is now out of a job.

For more than three decades, Mohammad Reza Hayati has been the face of the news on Iran’s state-controlled television.

Known to every Iranian, Hayati has presented all major domestic and international news stories — including the 1989 death of the founder of Iran’s Islamic republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini — in his deep voice while maintaining a calm demeanor.

But the 65-year-old newsman is now out of job after he publicly said he’s a devoted fan of prerevolutionary pop star Ebrahim Hamedi — better known as Ebi and often referred to as Iran’s Frank Sinatra.

After building a successful career in Iran in the 1970s, Ebi left his homeland for the United States and Europe after the 1979 revolution that established the Islamic regime.

Hayati, who’s referred to by some media as the “newsman” of the Islamic republic, spoke about his love for Ebi’s music in a discussion last month on Instagram.

“I am one of Ebi’s fans and to me the voice of Ebi is the voice of years of [great] memories,” Hayati said, adding that he has been listening to the now silver-haired soft pop singer for about 25 years. “I love all his songs.”

The comments apparently did not go down well with officials at the heavily censored state broadcaster, controlled by hard-liners, where anything and everything about the nearly 40-year reign of the shah of Iran is portrayed negatively.

“They contacted me and told me not to come to work for now,” Hayati told Iranian media over the weekend.

On June 8, Hayati told the semiofficial ISNA news agency that he hopes the decision will be reviewed and that he can go back to doing what he does best.

“I don’t have any problem with anyone — inshallah this problem is temporary,” he said.

Many Iranians noted the irony of a man who for so many decades carried the water for the Islamic establishment by delivering censored and slanted news now feeling the regime’s wrath.

Fleeing Iran

Many shah-era pop stars and actors were forced into exile following the 1979 revolution that resulted in the censorship of their work and a ban on solo singing by women.

Some of the artists who remained in Iran were prevented from working, including the legendary singer Googoosh, who did not perform in public until 2000 when she left Iran and moved to Los Angeles (which many Iranians have nicknamed “Irangeles” due to its large population of Iranians).

Despite the extreme censorship and efforts to portray them as promoting “decadent” Western culture, many prerevolutionary singers remain highly popular in Iran, even among those who were born after the revolution.

Millions still listen to the music of the now rather elderly crowd of crooners, whose songs can often be heard in cars, taxis, and at parties. Many Iranians also watch films of movie stars from the 1970s on satellite TV, online, or after buying them on the black market.

Many Iranians also travel to neighboring countries to attend concerts by Googoosh, Ebi, and other exiled singers. Ebi was recently the target of criticism after he held a concert in Saudi Arabia — Iran’s longtime rival in the region.

Writing on Instagram, Ebi said he was sad to learn that Hayati is not allowed to appear on Iranian TV anymore.

“I still don’t understand what crime I and artists like myself have committed — besides bringing people joy and singing about freedom — that even the people who show sympathy for us are being harassed,” Ebi wrote on his Instagram page, which has some 6.9 million followers.

The move to suspend Hayati was also criticized by the Iranian news site Asriran.com, which questioned the logic behind the decision.

“We see every day that more and more artists are moving away from the state broadcaster, particularly state TV,” the opinion piece on Asriran read.

“It seems that the state broadcaster is attempting to satisfy a certain group in the country and it doesn’t matter to them what other people say or think,” it added. “They ban, censor, and remove presenters to make it what they want.”

Hayati’s suspension comes weeks after a popular comedy series on state television angered hard-liners over scenes that resembled some from prerevolutionary hit television series that were banned in the Islamic republic.

In one of the sequences in the final episode of Paytakht 6, newlyweds ride a motorbike on the roads of northern Mazandaran Province, an image that has reminded many of an iconic scene in the 1975 romantic drama Hamsafar.

The criticism prompted the head of state-controlled television, Abdolali Ali Asgari, to order an investigation into whether a “mistake or negligence” was behind the questionable scenes in the very popular show, Paytakht, or whether they were the result of a “secret operation” by an unnamed enemy.

The TV series is an attempt by the Iranian state broadcaster to attract viewers who often choose to watch satellite TV and Western-made programs for entertainment instead of domestic channels that are often seen as less interesting.