Special to WorldTribune.com

By Gregory R. Copley, Editor, GIS/Defense & Foreign Affairs

Just how the shape of the new global strategic architecture will settle out as the framework for the 21st Century is still open to challenge, but the key dynamic — the initial door to that new world — is now being opened by a deliberately-orchestrated U.S.-North Korea confrontation.

What is emerging beyond this door is an overarching strategic alternative to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) démarche of “One Belt, One Road” dominance of the Eurasian and Indo-Pacific geopolitical space, and an alternative, or balance, to the PRC’s reach into Africa and the Americas.

The confrontation between U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean (DPRK) leader Kim Jong-Un is very much just between those two leaders, with the People’s Republic of China somewhat marginalized. Beijing is now fighting to find a path into this equation.

President Trump and Kim Jong-Un are now engaged in a profound, indirect negotiation in which each is now marshalling his own position as an end-game comes into perspective. What Kim seeks is an understanding with the U.S., not with the PRC; he wants a rôle on the world stage which is not dependent on China.

What the Trump-Kim initiative could lead to is:

1. U.S. recognition of the DPRK as a sovereign state and the exchange of ambassadors between the U.S. and the DPRK, with a concurrent commitment to a mutual reduction in threats;

2. U.S.-DPRK agreement to sign a peace treaty to end the Korean War, with the encouragement by the U.S. of the Republic of Korea (ROK) to also accede to that and with a formal recognition of the DPRK by the ROK;

3. Agreement that the ROK and its allies would formally end their goal of the reunification of the Korean Peninsula under a single Korean state. This, and the signing of a peace treaty, would enable a significant reduction of U.S. forces based in the ROK;

4. Agreement that the DPRK would formally position itself as a neutral state (the “Finlandization” solution), which would provide guarantees to the PRC that no hostile alliances would be created to bring U.S. or other foreign forces into the DPRK; and

5. The resultant prospect of opening logistical and trade links to and through the DPRK from the ROK, Japan, and others, linking through Tumangan (the DPRK border station) to Irkutsk, Moscow, and Western Europe, thus bypassing the PRC’s “One Belt, One Road”.

Another key driver — separate from the Trump-Kim match — is the now-substantive dialog between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe. President Putin visited Prime Minister Abe in Tokyo in December 2016; Prime Minister Abe visited President Putin in Moscow in April 2017. This dialog will ultimately also engage the United States and concerns not only security issues on the Korean Peninsula, but the longer-term logistical path from Japan through the Peninsula to the Russian railway links to Europe. The prospect also exists that the Japan-Russia rapprochement could see direct maritime freight links from Japanese ports to Vladivostok, to then transship by rail through Russia to Western Europe and the Atlantic ports.

The Trump thrust against the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 2017 should not be dismissed as an ill-conceived or accidental adventure.

It is Donald Trump’s “Commodore Perry/President Fillmore to Japan” (1853-54), or “Nixon to China” (1972).

Both Trump and Kim Jong-Un recognize the present theater — Talchum: the traditional Korean mask ritual — as a decisive event which could break the stalemate which has existed since the armistice of the Korean War on July 27, 1953.

The current script offers the prospect of saving the Kim dynasty and the DPRK (and at least bringing Pyongyang out of isolation), returning the U.S. to a new and different position in East Asia, and opening new ways of looking at the global framework.

The evolution of both President Millard Fillmore’s strategy toward Japan, and President Richard Nixon’s strategy to break the PRC away from the USSR and begin the path to the end of the Cold War, were each conducted in secret. The fact that there is no public comprehension — deliberately — of the purposes and desired outcomes of the “Trump to Pyongyang” initiative (which could end up being a “Kim to Washington” process; or a meeting in a neutral location) does not diminish the careful and orchestrated gavotte currently emerging.

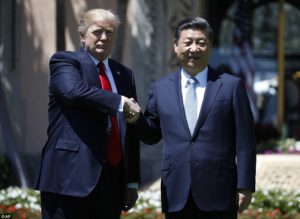

In all of this, the April 7, 2017, meeting in Florida between President Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping, followed by the swift U.S. military escalation toward the DPRK and the deployment of the USS Carl Vinson carrier strike group, has left Beijing as a partially-marginalized participant to events on its own doorstep. And, from Washington’s perspective, the military overtures (escalation) toward the DPRK needed to begin before the anticipated induction of Moon Jae-in as President of the Republic of Korea (South Korea: ROK), a known proponent of temporizing with the DPRK, on May 10, 2017.

Mr. Trump knew that he had to seize the moment — to dominate it — if it was to be the United States which spearheaded the opening-up (and managed the broader context) of the DPRK. President Trump sought to capture the concept of the great British Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke when he said: “The crowd is [already] in the street; I must go out in front of them if I am to be their leader.”

Significantly, this was a “crowd” which neither President Moon nor President Xi could seize; they were both too close and too vested. And it is only the U.S. which could offer Kim Jong-Un what he sought.

In the broader, longer-term context, it may emerge that the People’s Republic of China could become geopolitically constrained by this overarching process of events, beginning with the Trump DPRK initiative and ending with a more multi-polar framework opening trade and power avenues outside the “One Belt, One Road”.

The PRC would not be fully “contained” in the way in which the USSR and Soviet bloc was contained by the West during the Cold War, but it could be prevented from achieving the global dominance which Beijing has sought. There is now a pattern of developments occurring which the PRC cannot easily dominate, even though it attempts to continue its forceful diplomacy and structural achievements which made great headway during the global power vacuum which began with the erosion of U.S. global influence under the Presidency of George W. Bush (2001-09), and came to a head under President Barack Obama (2009-17).

Beijing’s current desperation to suppress any opposition to it came to a head on May 1, 2017, at a meeting in Perth, Western Australia, of the Kimberley Process group (which controls the international trade in diamonds). A deliberate, gang-like disruption was staged by PRC Government delegates at the opening of the meeting, shouting down the introduction to Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s opening of the meeting.

During the George W. Bush/Barack Obama period, the PRC sought to ensure the security of its strategic growth and global logistics chain by a series of infrastructural efforts, not only on the “One Belt, One Road” approach, but also to strategically constrain India and Australia — the significant Indian Ocean maritime powers — in order to neutralize threats in the Indian Ocean. This has already had the effect of building a new reactive framework to guard against the PRC militarily, which includes, for example, Japan, India, Australia, and the U.S., and with significant interest from Vietnam and some ASEAN member states. The PRC has attempted to break up this reactive framework by, for example, strengthening defense supply relationships and investment relations with Thailand, Pakistan, Myanmar, and so on.

In all this, the Trump Presidency, decried by the liberal global establishment before it even began to function, has, with its own Asian démarche, actually originated a coherent, creative process to halt U.S. strategic decline by balancing — rather than confronting — the PRC.

The Trump White House seems aware that the PRC’s greatest challenge is not the United States, but its own internal dynamic.

Beijing’s ambitious “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) — and the series of initiatives around it, from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), launched in 2016, to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) — has aimed to place the PRC at the economic center of the global geopolitical framework of the mid-21st Century. Beijing has, as a strategic goal, dominance over the Eurasian land communications, logistics, and trading network as well as the “maritime Silk Road” of ocean trade through the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean and the economies of Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Atlantic.

In other words, Beijing has attempted to force the belief that OBOR is the only framework for trade and security relationships dominating the Eurasian landmass and the associated maritime trade routes linking East, West, and South (ie, Africa and the Middle East). It also wants to ensure that this framework is under the absolute dominance of the PRC. In many respects, this is not only a strategic desire for dominance and security by Beijing; it is also an existential necessity if it is to obtain food security and therefore internal stability in the coming decades of population transformation within the PRC.

In China, and other parts of Asia, unfettered industrial expansion has led to widespread pollution of agricultural lands. The Wall Street Journal of July 27-28, 2013, noted: “Estimates from [PRC] state-affiliated researchers say that anywhere between eight percent and 20 percent of China’s arable land, some 25- to 60-million acres, may now be contaminated with heavy metals. A loss of even five percent could be disastrous, taking China below the ‘red line’ of 296-million acres of arable land that are currently needed, according to the government, to feed the country’s 1.35-billion people.” That report noted: “Removing heavy metals from farmland is a complicated process that can take years — time lost for farming. That is a chilling prospect for a government tasked with supporting 20 percent of the world’s population on less than 10 percent of the world’s arable land. Any major reduction in food security would hurt the Communist Party, which has staked its reputation in part on its ability to keep the country’s granaries full with minimal imports.”

A report in The New York Times of April 11, 2016, noted: “More than 80 percent of the water from underground wells used by farms, factories and households across the heavily populated plains of China is unfit for drinking or bathing because of contamination from industry and farming, according to new statistics that were reported by Chinese media … raising new alarm about pollution in the world’s most populous country.”

According to environmental statistics released by the PRC Government and quoted in the article, China’s use of underground water grew from 57-billion cubic meters a year in the 1970s to 110-billion cubic meters in 2009, providing nearly one-fifth of the country’s total supplies. In the arid north, underground supplies provided about two-thirds of water for domestic needs.

A 2014 PRC Government report had indicated that 59.9 percent of China’s ground water was polluted.

At the same time, water supplies in the PRC are declining, not only through over exploitation of ground water reserves, but also due to a declining supply reaching aquifers from the Tien Shan mountain snows.

There is mounting evidence in the public domain of the seriousness of the water and agricultural crisis facing the PRC, and the Government’s attempts to address the issue through land/water remediation, water transfer projects, desalination, and, presumably, more efficient use of irrigation techniques. Significantly, this was a threat to PRC stability which my colleague, Dr Stefan Possony, raised with me in conversations in the mid-1980s, highlighting the fact that it was the greatest threat to the stability of the PRC in the medium-term.

The threat, then, is rapidly declining water supply and quality, and rapidly diminishing agricultural capability and food supply at a time when urbanization is dramatically increasing the demand for water directly and for foods which require higher water content (such as beef). Between 1982 and 2015, the PRC’s urbanization population rose from 21 percent to 56 percent of the total population, with the expectation that urban areas will contain 60 percent of the PRC population by 2020.

Some relief is in sight for the PRC: its population growth rate has declined to 0.47 percent a year, and the population level (estimated at 1,382,710,000 in 2016) is now preparing to enter a period of decline in overall numbers. Formal estimates are that the population would peak by around mid-century, but the PRC population growth since World War II — the “baby boom” — has now, as with the rest of the world, shown that the current generation has not been replacing itself, and the “baby boomers” are now ageing and will soon disappear.

A substantial population decline could well be expected to occur in China within the coming one to two decades.

That would profoundly ease the food and water demands, but it would also decrease the demand for urban real estate, and therefore reduce asset valuations for urban property, in turn compounding national wealth levels and available credit.

Thus, the PRC and President Xi are faced with a short-term window of opportunity or need to acquire dominance over resources and food supply lines as quickly as possible to secure the future.

Agricultural imports from Central Asia will be critical, but — given the water shortages emerging there — insufficient. Russia would be a primary supplier, along with other states within the OBOR framework, including Iran and the African states linked to the PRC’s logistical framework.

All of this makes the PRC extremely vulnerable to international stability issues, and to domestic unrest issues.

“One Belt, One Road”, then, is the PRC’s existential strategy. But the question is whether the U.S. Trump initiative, beginning with the Korea re-balancing, can facilitate the already emerging alternatives to “One Belt, One Road”.

That would substantially reinvigorate and transform the U.S. global strategic posture and the U.S.-PRC balance into a far more nuanced framework. If that occurs, it would also reduce the prospects for direct U.S.-PRC military confrontation and pave the way for a new era of trade relationships with the PRC which would be centered more heavily around food supply as the principal trade commodity.

And yet there seems to be no hint of comprehension in most international governmental or media assessments of the Trump actions toward the DPRK. But they could change much of the global framework.