Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk

By Donald Kirk

Rodrigo Duterte was reputed as a killer long before his election as president of the Philippines five months ago. He countenanced the slaughter of hundreds of drug addicts and dealers while mayor of Davao, the major port city on the rebel-infested southern island of Mindanao, and has applauded the arbitrary killing of upwards of 2,000 more druggies as president.

Duterte’s brutality, though, doesn’t mean he’s interested in battling China on behalf of his country in the South China Sea. In fact, he’s confounded strategists in Washington by appearing to disavow the historic Philippine-American alliance, aligning with the Chinese while tossing out agreements with the U.S. He’s saying, in effect, “Yankee Go Home.”

If his declarations are puzzling, they are easy to understand. Beyond the “nationalist” pride, beneath the bravado, Duterte’s disparaging remarks about the traditional U.S. relationship raise questions about U.S. power everywhere in Asia.

First off, would the United States, despite its heralded “pivot” to Asia, risk an armed clash with China in the South China Sea?

That question has significance not just for Southeast Asia but for Northeast Asia too.

Sooner or later, the U.S. may have to decide whether to defend the Japanese on the Senkaku Islands, claimed by China, in the East China Sea ― and indeed how far to go for South Korea in a second Korean War in which China would surely side with its protectorate, North Korea.

Yes, the U.S. has shown the flag in the South China Sea by sending warships, notably Aegis-class destroyers, near the Spratly Islands where the Chinese have built a military base and lust after islets and reefs claimed by the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia.

American flag-waving demonstrates the view that China has indeed violated international law as the Permanent Court of International Arbitration in the Hague ruled in July.

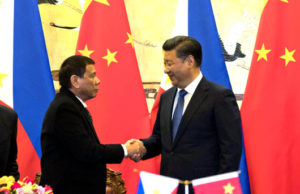

Duterte, by siding with China in his recent visit to Beijing, including a summit with President Xi Jinping, left no doubt that the ruling was a hollow victory. There’s no way the U.S. is going to go to war in the Spratlys. Nor, for that matter, is the U.S. interested in battling the Chinese for the Scarborough shoal, the rocky outcropping that lies within Philippine territorial waters north of the Spratlys and west of the main Philippine island of Luzon.

Clearly, if the Philippines is to get anywhere in retrieving the right of its fishermen to troll the waters of the Scarborough shoal, Duterte needs a deal with China. Only if the Philippines relinquishes its claim might China accept Philippine fishermen in and around the shoal, from which Chinese patrol boats have chased them.

The Philippines may also come to terms on the Spratlys by acknowledging China’s grip on what it’s got while holding on to one or two islets. Definitely any agreement under which the Philippines yields territory to China will be humiliating, but how can Duterte win concessions that might be beneficial to Philippine fishermen?

Over that question looms the whole issue of U.S.-Philippine defense arrangements.

Immediately at stake is the U.S.-Philippine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement under which the Philippines agreed two years ago that U.S. troops might rotate in and out of five Philippine bases. The deal evokes memories of the era in which two of America’s largest overseas bases ― Clark in Angeles City north of Manila and the naval base on Subic Bay on the South China Sea ― guaranteed Philippine security.

The U.S. had to pull out of Clark and Subic in the early 1990s after the Philippine Senate refused to renew the lease on the bases in a storm of “nationalist” sentiment. The recent defense agreement portended a shift back to the old days, but Duterte has said he doesn’t want to see American forces anywhere on Philippine soil.

Now the future of the U.S.-Philippine alliance is up in the air. Duterte did say that he did not mean to “sever” relations with the U.S. when he spoke of “separation” of the U.S. from the Philippines, but obviously he does not see Washington as capable or committed to guaranteeing security against the rising power of China.

For years the U.S. has provided aid and advice for the Philippines’ armed forces, riddled by inefficiency and corruption, as they battle tenacious Communist and Islamic guerrillas. Considering the legacy of U.S.-Philippine friendship, the Chinese may have difficulty replacing the Americans as aid-givers. If China does provide massive aid, Filipinos, wary of the economic grip of a powerful Chinese minority, may fear subjugation or subservience.

The details vary, but similar questions arise all around the periphery of China. Who wants the Chinese imposing terms and conditions from the Korean peninsula to Southeast and South Asia?

While shouting anti-American slogans, “nationalists” and populists should be careful what they wish for before kowtowing to Beijing.

Donald Kirk, author of “Looted: the Philippines After the Bases” and “Philippines in Crisis: U.S. Power versus Local Revolt,” is at kirkdon4343@gmail.com.