Barring a really major blunder – such as revealing that he was born in Lower Volta or endorsing inter-species marriage (the next big civil-rights issue) – this election is beginning to look like it’s Mitt Romney’s to lose.

On the morning after the third and mercifully last presidential debate, nearly all the major polls show the race tied or Mr. Romney narrowly ahead. The Gallup Poll, the oldest such, dating from 1936, shows a Romney lead of 6 points, well outside the margin of error.

Five of the eight major polls averaged Monday by RealClearPolitics.com show Mr. Romney up by margins ranging from 2 to 6 points. The polls in the important swing states, particularly Ohio, are drawing close as well.

We’ve reached the tipping point in the campaign, when voters become bored with the blah blah and want most to be put out of their misery. The constant barrage of television commercials has made it unsafe to turn on a TV set lest a viewer get caught in the crossfire between Channel 7 and Channel 4. There’s a public-opinion poll to suit every partisan hope for change: If you don’t like Battleground there’s Quinnipiac. If your taste runs to something more imaginative, there are polls by Zogby, a dozen colleges and maybe even one somewhere by the Sharia School of Law and Anglo-Saxon Jurisprudence. Everybody wants to know who won, even if we haven’t got there yet.

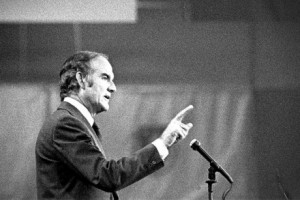

What is clear is that we’re as divided as we ever were, and there’s scant hope for a landslide that settles once and for all what kind of country we want to be. We had a blowout election in 1972, when George McGovern lost 49 states, winning only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, and here we are again. It’s called democracy, and ours is particularly noisy, robust, unpredictable – and long-running.

Loser or not, no one ever put an asterisk against George McGovern’s origins deep in America’s heartland, his unreserved love for his native land or his courage under fire. He flew a B-24 Liberator on more than two dozen bombing missions against the Nazis, twice bringing his battered ship home on a wing and a prayer. He won the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal and went home to South Dakota to marry his high-school sweetheart, Eleanor, who, like so many young women of those years, waited, afraid to take a deep breath, for her soldier’s return home from the hill. He studied for the Methodist ministry at Dakota Wesleyan College, where no one tried to destroy his faith, and later reluctantly traded the cloth for politics. But he never abandoned Christ’s commandment to look after the poor, the hungry, “the least of these.”

I ribbed him unmercifully in my column for his sometimes-goofy left-wing politics, the presidential candidate who had sealed his fate as big-time loser when he proclaimed that he would “crawl on my knees to Hanoi” to end the Vietnam War. There’s just something about bowing and crawling that Americans don’t like. He wrote to me occasionally to needle The Times for the editorials and for things I wrote. One day my phone rang and a familiar voice said: “This is the man you call ‘Mr. Magoo,” and I’d like to ask you to lunch.” We became friends, neither of us softening the other’s politics, but Baptist and Methodist preachers’ sons talking politics, war, peace and sometimes a little theology. He was regarded by Democrat, Republican, liberal and conservative alike as one of the most decent men in the United States Senate. I soon understood why.

Mr. Magoo, who died Sunday, age 90, had the rare gift of humility. When he learned as a Connecticut innkeeper how government regulators conspire to thwart a businessman’s thrift and industry, he ruefully conceded in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal that if he had known first-hand about the difficulties the government imposes, “that knowledge would have made me a better U.S. senator and a more understanding presidential contender.” (Such good advice for Barack Obama.)

He once recalled how a man and a little boy came up to him at the Minneapolis airport a few days after the 49-state blowout of ’72. “I voted for you and I’m really sorry how it turned out,” the man told him. Then the little boy of about 7 piped up: “Yeah, but don’t feel bad. Coming in second is pretty good.”

Mr. Magoo, R.I.P.

Wesley Pruden is editor emeritus of The Washington Times.