Special to WorldTribune.com

By Bill Federer, July 20, 2020

In the decades prior to the Revolutionary War, tensions arose between the two largest global powers: Britain, led by King George II, and France, led by King Louis XV.

Because of their alliances with other nations, fighting escalated into the first global war — the Seven Years War, or as it was called in America, the French and Indian War.

The conflict included every major power in Europe as well as their colonies from the Caribbean, to India, to the Philippines, and to Africa.

Over a million died.

It was sparked by the ambush in 1754 of a French detachment in the Ohio Valley by British militia led by 22-year-old Virginia Col. George Washington.

During this crisis, people turned to Christ. The Great Awakening Revival swept through the American colonies.

A notable dissenting preacher, Samuel Davies, spread revival across racial lines and was heard by many in Virginia, including Patrick Henry, who credited Davies with “teaching me what an orator should be.”

Rev. Davies regularly invited hundreds of slaves to his home for a Bible study on Saturday evenings, their only free time, and taught them hymns and how to read.

Realizing the importance of education, Davies helped found Princeton University, and was chosen its president after Jonathan Edward’s sudden death.

In 1755, 1,400 British troops marched over the Appalachian Mountains to seize French Fort Duquesne, near present day Pittsburgh.

One of the wagon drivers for the British was 21-year-old Daniel Boone.

On July 9, 1755, they passed through a deep wooded ravine along the Monongahela River eight miles south of the fort. Suddenly, they were ambushed by French regulars and Canadians accompanied by Potawatomi and Ottawa Indians.

Not accustomed to fighting unless in an open field, over 900 British soldiers were annihilated in the Battle of the Wilderness, or Battle of Monongahela.

Col. George Washington rode back and forth during the battle delivering orders for General Edward Braddock, who was the Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America.

Gen. Braddock was trying to get his soldiers into a formation typical of European warfare, which tragically made them an open target for the French and Indians, who were firing from behind trees.

Eventually, every British officer on horseback was shot, except Washington. Gen. Braddock was mortally wounded. Washington carried Braddock from the field.

Braddock’s field desk was captured, revealing all the British military plans, enabling the French to surprise and defeat British forces in succeeding battles at:

- Fort Oswego,

- Fort William Henry,

- Fort Duquesne, and

- Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga).

The terrible British losses convinced the Iroquois tribes of Senecas and Cayugas to switch their allegiances to the French.

Before he died, Gen. Braddock gave Washington his battle uniform sash, which Washington reportedly carried with him the rest of his life, even while Commander-in-Chief and President. Washington presided at the burial service for Gen. Braddock, as the chaplain had been wounded.

Braddock’s body was buried in the middle of the road so as to prevent it from being found and desecrated.

Shortly after the Battle of Monongahela, George Washington wrote from Fort Cumberland to his younger brother, John Augustine Washington, July 18, 1755:

“As I have heard, since my arrival at this place, a circumstantial account of my death and dying speech, I take this early opportunity of contradicting the first, and of assuring you, that I have not as yet composed the latter. But by the All-Powerful Dispensations of Providence, I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation; for I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me, yet escaped unhurt, although death was leveling my companions on every side of me!”

Reports of the defeat of Gen. Braddock at the Battle of Monongahela spread across the country.

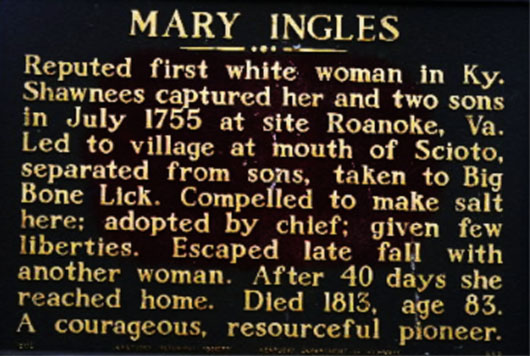

A short time later, on July 8, 1755, a band of Shawnee Indians massacred the inhabitants of Draper’s Meadow, Virginia.

Mary Draper Ingles was kidnapped and taken as far away as Kentucky and Ohio. At one point during her captivity, she overheard a meeting that the Shawnee had with some Frenchmen.

They described in detail the British defeat in the Battle of Monongahela at Duquesne, and how the Indian Chief Red Hawk claimed to have shot Washington eleven times, but did not succeed in killing him.

After several months, Mary Draper Ingles escaped in mid-winter, as recorded in her biography, and trekked nearly 1,000 miles back home.

Fifteen years after the Battle of Monongahela, George Washingto n and Dr. Craik, a close friend of his from his youth, were traveling through those same woods near the Ohio river and Great Kanawha river.

There they were met by an old Indian chief, who addressed Washington through an interpreter:

“I am a chief and ruler over my tribes. My influence extends to the waters of the great lakes and to the far blue mountains. I have traveled a long and weary path that I might see the young warrior of the great battle. It was on the day when the white man’s blood mixed with the streams of our forests that I first beheld this Chief. I called to my young men and said, mark yon tall and daring warrior? He is not of the red-coat tribe-he hath an Indian’s wisdom, and his warriors fight as we do-himself alone exposed … . Quick, let your aim be certain, and he dies. Our rifles were leveled, rifles which, but for you, knew not how to miss — `twas all in vain, a power mightier far than we, shielded you. Seeing you were under the special guardianship of the Great Spirit, we immediately ceased to fire at you. I am old and soon shall be gathered to the great council fire of my fathers in the land of shades, but ere I go, there is something bids me speak in the voice of prophecy …”

The Indian Chief continued:

“Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man and guides his destinies — he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire. I am come to pay homage to the man who is the particular favorite of Heaven, and who can never die in battle.”

The account of an Indian warrior spread, that:

“Washington was never born to be killed by a bullet! I had seventeen fair fires at him with my rifle and after all could not bring him to the ground!”

The qualities of faith, virtue and discipline were evident during this early period of George Washington’s public career, as seen in his actions and correspondence.

The young Col. George Washington wrote from Alexandria, Virginia, to Governor Dinwiddie, Feb. 2, 1756:

“I have always, so far as was in my power, endeavored to discourage gambling in camp, and always shall while I have the honor to preside there.”

Colonel Washington wrote from Winchester, Virginia, to Governor Dinwiddie, April 18, 1756:

“It gave me infinite concern to find in yours by Governor Innes that any representations should inflame the Assembly against the Virginia regiment, or give cause to suspect the morality and good behaviour of the officers … I have, both by threats and persuasive means, endeavored to discountenance gambling, drinking, swearing, and irregularities of every kind; while I have, on the other hand, practised every artifice to inspire a laudable emulation in the officers for the service of their country, and to encourage the soldiers in the unerring exercise of their duty.”

Washington issued the following order while at Fort Cumberland in June of 1756:

“Colonel Washington has observed that the men of regiment are very profane and reprobate. He takes this opportunity to inform them of his great displeasure at such practices, and assures them, that, if they do not leave them off, they shall be severely punished. The officers are desired, if they hear any man swear, or make use of an oath or execration, to order the offender twenty-five lashes immediately, without a court-martial. For the second offense, he will be more severely punished.”

In 1756, Col. George Washington issued the order:

“Any soldier found drunk shall receive one hundred lashes without benefit of court-martial.”

About a year after Gen. Braddock’s defeat, Col. Washington wrote to Governor Dinwiddie from Winchester, Virginia:

“With this small company of irregulars, with whom order, regularity, circumspection, and vigilance were matters of derision and contempt, we set out, and by the protection of Providence, reached Augusta Court House in seven days without meeting the enemy; otherwise we must have fallen a sacrifice through the indiscretion of these whooping, hallooing, gentlemen soldiers.”

On Sept. 23, 1756, Col. Washington wrote to Gov. Dinwiddie from Mount Vernon:

“The want of a chaplain, I humbly conceive, reflects dishonor on the regiment, as all other officers are allowed. The gentlemen of the corps are sensible of this, and propose to support one at their private expense. But I think it would have a more graceful appearance were he appointed as others are.”

On Nov. 9, 1756, Colonel Washington wrote to Governor Dinwiddie:

“As to a chaplain, if the government will grant a subsistence, we can readily get a person of merit to accept the place, without giving the commissary any trouble on the point.”

On Nov. 24, 1756, Colonel Washington wrote to Gov. Dinwiddie:

“When I spoke of a chaplain, it was in answer to yours. I had no person in view, though many have offered; and I only said if the country would provide subsistence, we could procure a chaplain, without thinking there was offense in expression.”

On April 17, 1758, after Gov. Dinwiddie was recalled, Col. Washington wrote from Fort Loudoun to the President of the Council:

“The last Assembly, in their Supply Bill, provided for a chaplain to our regiment. On this subject I had often without any success applied to Governor Dinwiddie. I now flatter myself, that your honor will be pleased to appoint a sober, serious man for this duty. Common decency, Sir, in a camp calls for the services of a divine, which ought not to be dispensed with, although the world should be so uncharitable as to think us void of religion, and incapable of good instructions.”

On July 20, 1758, in a letter to his fiancee, Martha Dandridge Custis, Col. George Washington wrote from Fort Cumberland:

“We have begun our march for the Ohio. A courier is starting for Williamsburg, and I embrace the opportunity to send a few lines to one whose life is now inseparable from mine. Since that happy hour when we made our pledges to each other, my thoughts have been continually going to you as to another Self. That an All-Powerful Providence may keep us both in safety is the prayer of your ever faithful and ever affectionate Friend.”

On Jan. 6, 1759, George Washington was married to Martha Dandridge Custis by Rev. David Mossom, rector of Saint Peter’s Episcopal Church, New Kent County, Virginia.

After having settled at Mount Vernon, George Washington became one of the twelve vestrymen in the Truro Parish, which included the Pohick Church, the Falls Church, and the Alexandria Church.

The old vestry book of Pohick Church contained the entry:

“At a Vestry held for Truro Parish, October 25, 1762, ordered, that George Washington, Esq. be chosen and appointed one of the Vestry-men of this Parish, in the room of William Peake, Gent. Deceased.”

In his diary, George Washington recorded his attendance at numerous Church and Vestry meetings.

On Feb. 15, 1763, the Fairfax County Court recorded:

“George Washington, Esq. took the oath according to Law, repeated and subscribed the Test and subscribed to the Doctrine and Discipline of the Church of England in order to qualify him to act as a Vestryman of Truro Parish.”

Thirteen years later, General George Washington stated, July 2, 1776:

“The time is now near at hand which must probably determine whether Americans … are to have any property they can call their own; whether their houses and farms are to be pillaged and destroyed, and themselves consigned to a state of wretchedness from which no human efforts will deliver them. The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us no choice but a brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore to resolve to conquer or die.”