Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk, EastAsiaIntel.com

By Donald Kirk, EastAsiaIntel.com

North Koreans some years ago had an unusual way of acquiring professional expertise in teaching people foreign languages.

Rather than advertise for teachers, they kidnapped native speakers. Most of them were Japanese, but they also captured likely candidates from Europe and the Middle East.

Robert Boynton, a professor of magazine journalism at New York University, more or less explains what the North Koreans were doing in his book, “The Invitation-Only Zone: The Extraordinary Story of North Korea’s Abduction Project,” but important questions go unanswered.

Absolutely the most compelling is how many more kidnap victims remain in North Korea. Most Japanese are convinced the North Koreans are holding hundreds whom teams of agents for the regime have grabbed off beaches, picked up in parks or inveigled into meetings under false pretenses.

Why would a country resort to kidnapping? That’s one of the many mysteries about North Korea, about the isolation and delusions of leaders who got the idea the best way to find the talent they needed was to drag people from whatever they were doing, hustle them onto boats and put them to work.

It didn’t seem to occur to them to hire real teachers on regular contracts, inviting them to stay for a year or two before going home.

No, the North Koreans had other ideas. They wanted these teachers to be able to train young North Koreans to be able to speak foreign languages well enough to serve as spies and agents.

They also believed they could steal their identities for fake passports, and they may have had the notion of some of them having children who in turn could serve as spies.

Exactly what was going on in the mind of the late “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-Il, who had to have ordered the kidnappings, is not clear, but then we don’t understand a great deal about what he or his son, current leader Kim Jong-Un, or the people around them are thinking.

That leads to another question about this whole saga. As the title indicates, all the victims were placed in houses in what were called “invitation-only zones” ― special areas where they might appear to live normally.

Fencing surrounded these zones, however, keeping them on the inside while preventing any contact with people on the outside.

You have to wonder about the depth of control of a regime that gets away with kidnapping people from abroad and then hermetically sealing them away from anyone who might find out about them. How did the North Koreans do it?

After years shrugging off reports of missing people, defector stories eventually convinced Japanese authorities of what was happening.

On a mission to Pyongyang in 2002, Japan’s former prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi, persuaded Kim Jong-Il to let a few of them return, but they were the lucky ones.

Boynton tells the stories of romantic couples hustled onto boats on dark nights and spirited to North Korea without knowing the other had been kidnapped until maybe a year later they were thrown together and married.

Some seem to have resigned themselves to their fates but not all.

Megumi Yokota, kidnapped on her way home from badminton practice, suffered severe depression, so much so that Boynton tells us she was put in a mental hospital.

That’s a revelation in itself. Who knew the North Koreans had mental hospitals? And who knows what goes on in them? Considering the craziness of North Korean society, you have to wonder how they judge who’s sane and who’s not.

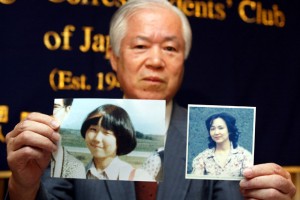

The North Koreans claim poor Megumi committed suicide, but Boynton omits the story of the bones they returned to Japan as evidence that she was dead. It turned out they were dog bones, leading some people, notably her parents, to think she’s still alive.

He also skips the detail that her captors had assumed she was in her late teens. In fact, she was 13, emotionally dependent on her parents, an age when the trauma of the experience might be irreversible.

Why, however, did the North Koreans seize mainly future language teachers? Why not engineers, technical people, scientists and doctors? They did kidnap a South Korean actress and her film director ex-husband in Hong Kong in 1978.

Amazingly, those two got out eight years later when Kim Jong-Il decided he could trust them enough to let them attend a film festival in Vienna. Big mistake. They eluded their minders and showed up at the U.S. embassy.

That story is well known, but Boynton recounts other stories too. There’s the saga of a Japanese cook thinking he was going to a new job in Beijing. The agent who hustled him onto the boat to North Korea in 1980 was arrested as he tried to enter South Korea using the cook’s passport.

Boynton neglects to tell us that the late President Kim Dae-Jung, in keeping with his Sunshine Policy, ignored Japanese requests to interview the agent before freeing him along with 62 others who’d been jailed in the South, mostly for spying.

Nor do we find out what happened to the cook. One day perhaps the real truth will come out and Boynton will be able to write a sequel to this harrowing but unfinished tale of duplicity, cruelty ― not to mention utter stupidity at the highest levels in Pyongyang.

Donald Kirk is the author of “Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae-jung and Sunshine.” He’s reachable at kirkdon4343@gmail.com.