Special to WorldTribune.com

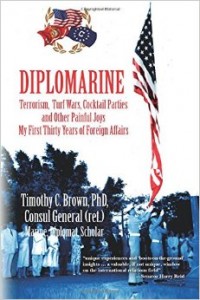

[Following is an excerpt from the new book, DIPLOMARINE]

Timothy C Brown, PhD.

There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of books on America’s foreign policies as seen from virtually every angle save one — that of the poor bastards charged with trying to make them work. In ‘Diplomarine’ I try to fill this gap, at least partially, by telling what the world of foreign affairs looked like to me from the bottom up over a course of thirty years, first as an enlisted Marine and then as a career diplomat.

My baptism into the foreign affairs community came in 1956 in Managua, Nicaragua during my first Marine enlistment. The Cold War was in full swing; Nicaraguan caudillo Anastasio “Tacho” Somoza García had just been assassinated; revolutionaries were preparing to launch armed insurgencies throughout Central America; and I was a wide-eyed innocent on his first adventure abroad.

In 1964, toward the end of my second Marine enlistment I took and, to my surprise, passed the Foreign Service Officer Written and Oral Entrance Examinations and was offered a commission. Had I immediately accepted I would have become the only officer in the Foreign Service without a college degree, and that would have put me at a severe competitive disadvantage. So, at the State Department’s urging, in June of 1964 I decided to leave the Corps, go back home to Reno, and try to finish the last three semesters of my undergraduate studies in nine months. My long-suffering wife, Leda, now expecting for the fourth time, went ahead with Barbara, Rebecca and Tamara, our three daughters, to fi x up a small house my mother had agreed to let us live in. I gave her our last $100, with which she managed to buy enough Salvation Army furnishings to make it habitable. Despite being six months pregnant, she even managed to paint its interior.

After that, the least I could do was finish my undergraduate studies, which I did. Ten months later in June of 1965, degree in hand, I received my FSO commission.

For the next twenty-seven years I was to be a Foreign Service officer, a career diplomat. During the first fourteen, I served consecutively in Israel, Spain, wartime Vietnam, Mexico, Paraguay, El Salvador, and the Netherlands.

During my three decades as a practitioner of Machiavelli’s dark arts, I spent more time in war zones as a diplomat than Marine. If my readers take away just one lesson from the tales told in ‘Diplomarine’, I hope it will be that implementing foreign policies in the field, whether in a Marine uniform or a diplomat’s suit and tie, is exceptionally complex, always challenging and, on occasion, very dangerous. During my diplomatic years, the gourmet dinners, swank cocktail parties and quiet afternoons on topless beaches, for which diplomacy is best known, were repeatedly interrupted by wars, terrorist bombings, assassinations, narco-mobs, partisan confrontations, bureaucratic turf wars, politics, and other forms of organized mayhem. As they say in rodeo, it was one hell of a ride.

‘Diplomarine’ ends with my departure from Martinique for what was to be by far the most sensitive, dangerous, and controversial assignment of my diplomatic career. …

While Special Liaison Officer (SLO) to the Contras in Central America I had depended on major studies of them written by the intelligence community that were not merely dead wrong but reached conclusions that were the precise opposite of the truth. One study, prepared for inclusion in a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) by the State Department’s Office of Intelligence, was so far off the mark that it might as well have been written in Havana or Managua by the Contra’s enemies, not in Washington by its supposed friends.

Other earlier, but equally erroneous reporting, may well have misled President Reagan, CIA Director Bill Casey, Congress, and many others, just as later reporting misled me, for one simple reason. They believed, as I did, what they were told by the intelligence community.

During my post-Foreign-Service doctoral research, I was able to thoroughly document that, far from the murderous thugs of the “Black Legend of the Contras” painted by the media and anti-Contra activists during the Contra War, almost 98 percent of the Contras were just “un att erro de campesinos bien encachib’aos, (just a whole bunch or really pissed off peasants). This was exactly the opposite of what our intelligence community believed they were.

This made me wonder if we might not have been as wrong about the other side of Central America’s recent civil wars as we had been about the Contras. If we hadn’t even known who our own allies were, were we also wrong about our enemies?

So, once I had my PhD in hand, I launched on yet another quest for understanding that took me back, of all places, to my wife’s childhood home in San José, Costa Rica to talk with one of her closest neighbors, Plutarco Hernández Sancho. I’d met Plutarco during our Sept. 12, 1958 wedding reception. But, since he was just fourteen years old at the time, I hadn’t paid much attention to him other than to notice that he kept making goo-goo eyes at my bride.

During the intervening years, Pluti, as I now call him (we have since become close friends), had gone on to become a major player on the revolutionary side of Central America’s civil wars, especially Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolution. In fact, Manuel Jirón, in his 1986 “Quién es Quién en Nicaragua” (Who’s Who in Nicaragua, Radio Amor, San José, Costa Rica), dedicates more space to Plutarco than to Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and his brother, Gen. Humberto Ortega, combined. During my years as Thai Intelligence Linguist, Plutarco was organizing Costa Rica’s first Communist Youth League.

During my years as a junior diplomat, he spent several years studying at Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow, a year being trained in guerrilla warfare at Campamento Cerro, just outside Havana, Cuba, and an additional six months in North Korea, doing advanced studies in how to subvert a country under the personal tutelage of Kim Il-Sung. And during my years as a mid-career diplomat he spent sixteen years as a National Director of Nicaragua’s Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN).

After giving me a fairly candid oral history of his life as a revolutionary, which I dutifully videotaped, Plutarco then went the extra mile and introduced me to five key members of his Cold War cell. Each, in turn, allowed me to videotape their oral history.

And therein lays yet another story I’m reserving for the future.

See Part II: The joys of enforcing the Cuba Embargo.

More information about Tim Brown and ‘DIPLOMARINE: Terrorism, Turf Wars, Cocktail Parties and Other Painful Joys My First Thirty Years of Foreign Affairs’ can be found at the author’s site at Diplomarine.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login