Special to WorldTribune.com

Almost all decisive strategic victories — winning the peace, not just the battle — derive from the adoption of game-changing capabilities, as well as strategic depth. Competing through linear development of old approaches is expensive and dangerous, especially when budgets are tight.

Gregory R. Copley, GIS/Defense & Foreign Affairs

Chill winds are sweeping through the Pentagon as U.S. military leaders contemplate the point at which they have now arrived: They cannot deliver decisive military force against the People’s Republic of China (PRC) short of total war, the commitment of inter-continental ballistic missiles. Even there, victory, even pyrrhic victory, is debatable.

The U.S. and the PRC are not at war, and do not contemplate the near-term eventuality of such a situation, but each regards the other as the capability against which it must prepare. They also compete, regardless, for strategic leadership.

The U.S. and the PRC are not at war, and do not contemplate the near-term eventuality of such a situation, but each regards the other as the capability against which it must prepare. They also compete, regardless, for strategic leadership.

In some respects, the nation-state with the greatest prestige can win a de facto victory; it was through such a psycho-political denouement that the Cold War was won by the West, and by the U.S.

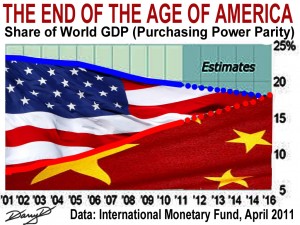

It is now apparent that the United States is not only declining in real military and economic capability; it is declining in prestige, compounded by one strategic mis-step after another. The increasing clarity of the decline in U.S./Western military capability vis-à-vis the PRC is not just in absolute terms, but in points where it matters. The U.S. and its allies lack coercive influence over many of the key strategic actions which Beijing wishes to take. And lack the military capability to challenge the PRC’s territorial dominance.

In short, the evolution of Western weapons systems and major defense platforms has, driven by the U.S., led the West down a blind alley. This was the inevitable path of a power which has not had to face an existential challenge for a protracted period. It continued to develop its technologies and reinforce the doctrine of the wars which it had won long past; it has not been challenged — at least not sufficiently — to develop technologies and practices which eclipse, rival, or replace its once successful technologies and doctrine.

Rival aspirants for power, however, have had no option but to seek ways to bypass or negate those Western strengths which were built and compounded with the wealth of dominance over decades.

There were many triggers from the early 1990s as to why the PRC, in particular, was stirred into competitive creativity to counter U.S. strategic capabilities.

The desire for economic power was one such incentive, and this began with the demise of Mao Zedong and the rise of Deng Xiaoping beginning in 1978. What took this growing economic power, however, to seek strategic self-sufficiency and power projection dreams was, however, more a fear of what emerged as the threat of unfettered U.S. military intervention. This, for Beijing, seemed to take on new urgency with the war by U.S. President Bill Clinton against Serbia in 1999. On May 7, 1999, during the NATO bombing of Belgrade (during Operation Allied Force), five U.S. JDAM guided bombs hit the PRC embassy in what was perceived as a deliberate act.

There were other factors, but this galvanized Chinese thinking, and the need to gain sufficient strategic prestige to ensure that the PRC’s future was not again ever constrained by the U.S. As a result of all the factors, the PRC developed the capabilities to ensure that it could defend its territory and immediate geographic region, and could project power abroad.

Similar fears and perceived slights now galvanize Russian strategic planning. Western dismissals of Russian (or, in the past, PRC) capabilities or prestige merely serve to galvanize a spirit of competitiveness and a search for dignity. A resurgence not perceived as possible by those assessing their rivals on the basis of a linear extrapolation of recent observations thus becomes possible. The Israeli dismissal of Egyptian capabilities after the 1967 Six Day War led directly to the Egyptian resurgence and successes of the October 1973 War.

Now, after the U.S. challenge over Ukraine, Russia plans a major expansion of its nuclear deterrent, and the rebuilding of its strategic and long-range aviation assets and its precision weapons, and much more in the 2016-25 time frame. It had already committed some $540 billion to its 2011-20 defense investment plan, including the development of its “future long-range air system” (the PAK-DA).

The lesson here is to be humble in victory and to transform former enemies into friends. The U.S. did not learn that lesson following the end of the Cold War, much as the architects of that victory — U.S. President Ronald Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher — sought a post-Cold War rapprochement.

Today, the development of PRC weapons and capabilities, in particular, means that the great U.S. weapons platforms — particularly carrier battle groups and sea and land-based strike aircraft — lack the ability to penetrate PRC defenses to sustain operations against the Chinese heartland, or to sufficiently support U.S. allies in Southeast Asia or East Asia.

Is the U.S. answer merely to attempt to step up the range of its carrier-based F-35 aircraft and also to await the commissioning of the still-undefined LRS-B (long range strike bomber? Or somehow extend the range of the Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS)? This is the linearist approach, and fails to address the improvements in PRC air defenses or the unaddressed vulnerability of U.S. land- and sea-based assets in the Pacific.

The only way to play catch-up is not to play that game at all, but to switch to leap-frog. Only by leap-frogging the capabilities of the PRC and others can the U.S. and the West hope to regain strategic leadership. But it is not merely about “abandoning the battleships”, and embracing new technologies; it is about rebuilding strategic prestige and flexibility.

I stressed, in UnCivilization: Urban Geopolitics in a Time of Chaos, that Western civilization had become sclerotic through entitlement, bureaucracy, political correctness, and taxation.

The ability to rapidly evolve new technologies is diminished by the decline in scientific and industrial flexibility and constraints against investment.

Clean-sheet thinking on defense is a start, but if strategic momentum is to be achieved it must include freeing economies, restoring free speech (and ending hysteria-inducing political correctness), and re-evaluating how to deal with allies and rivals.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login