Special to WorldTribune.com

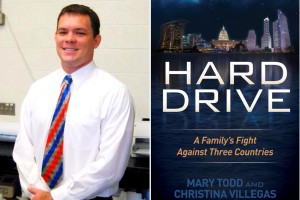

[First of three excerpts from the new book, Hard Drive.]

On June 24, 2012, Dr. Shane Truman Todd, a young American engineer, was found hanging in his Singapore apartment, just a week before his scheduled return to the United States. Although Shane had repeatedly expressed apprehension that his work with a Chinese company might compromise U.S. security, authorities immediately ruled his death a suicide. Upon arriving in Singapore, his family realized the evidence suggested not suicide, but murder. Hard Drive: A Family’s Fight against Three Countries is the captivating story of Shane’s mysterious death and his family’s grueling battle to reveal the truth.

Chapter 1: The Small Dark Room

The Singapore Police Station, June 27, 2012. Investigating officer (IO) Khal ushered us into a scanty, putrid green room with no windows or pictures hanging on the wall. It felt like an interrogation room for criminals, not a room to console anguished, grieving parents. IO Khal took the chair behind the desk, offering Rick and me the two chairs facing it. There was barely enough room for the fourth chair that was brought from another room for Traci Goins, Vice Consul to the American Embassy. Rajina, the assistant in training, was crammed in the corner and forced to stand for the duration of the meeting, which lasted for several hours. The room was so cramped that when anyone needed to leave, everyone had to stand up and rearrange the chairs to create enough space to open the door.

Khal was a twenty-three year old police rookie, with a constant wide, sloppy grin, making it appear as if he were about to blurt out the punchline to a joke, rather than convey the worst news any parent could ever hear. He started off the meeting bluntly by asking, “Do you want to know how your son killed himself?” We numbly nodded our heads. Khal began methodically reading from a typed sheet of paper a well-written, detailed description of how they concluded our first-born son Shane Truman Todd took his own life.

The description read more like a novel than a report written by the police: “First he fashioned an elaborate hanging apparatus that included drilled holes into the bathroom wall, bolts, pulleys, and ropes wrapped around the toilet and slung over the bathroom door. On the outside of the closed bathroom door he put the noose around his neck, stood on a chair and dropped to his death.”

As I listened to the graphic depiction of how my son allegedly killed himself, I was dismayed: “It would take an engineer to design and build something so intricate…someone brilliant like Shane. Is it possible that my son could have taken his own life?”…

After reading the description of suicide, Detective Khal informed us that Shane had written two suicide notes: “I found the suicide notes in Shane’s apartment on his open computer that was sitting on top of his bed. No one has read them before now. I printed up a copy for each of us. Would you like to read them, and is it all right if I give Ms. Goins and myself a copy?” With our approval, he ceremoniously handed out the notes.

[Warning: The ‘Pacific Era’ Has Arrived]

As my brain absorbed the words I was reading, I felt my first sense of joy since learning of my son’s death. The style of writing was completely foreign to me. The notes — addressed “Dear Everyone,” “Dear Mom and Dad,” “Dear John, Chet, and Dylan,” “Dear Shirley,” and “Dear Friends” — were written methodically, without emotion, as if the author were following a checklist of points that needed to be covered. They were void of the tortured despair that a man would express before ending his life. The notes did not contain one memory that held an important spot in our family’s history. There were only two cold sentences to his three brothers, John, Chet, and Dylan, whom he loved beyond measure. The vernacular was not my son’s and one of the memories, “drinking Shirley temples on the beach,” never happened. I knew, right then and there, that if my son did not write the suicide notes, he did not commit suicide. It wasn’t until almost a year later that my initial conviction about the notes was scientifically substantiated.

With a forceful look, I captured Khal’s eyes and calmly handed the notes back to him: “My son might have committed suicide, but he did not write these notes.”

* * *

Two days later, Rick and I, along with two of our sons, John and Dylan, anxiously headed to the apartment where Shane had lived and died. As I climbed the long, narrow staircase to Shane’s apartment, my whole body was shaking, and my heart was pounding. My thoughts kept returning to the detailed description of how Shane supposedly hanged himself, so I was unnerved when we opened Shane’s apartment door and realized it was unlocked and there was no crime-scene tape or signs of dusting for fingerprints…

With the sheer determination of a mother on a mission, I made a beeline for Shane’s bathroom. As I looked into the bathroom, I was perplexed and shocked. Nothing I saw matched IO Khal’s description. “Oh my gosh, John, come quickly, you’ve got to see this,” I yelled.

John ran to me and we both began to exclaim, “Where are the bolts, the ropes, and the pulleys? Why is the toilet not across from the door as Khal described it?” Perplexed, we ran our hands over the marble walls searching for holes that might have been patched, looking for anything that would back up what Khal had told us. Nothing!…

I called Khal immediately and asked him to come to Shane’s apartment to explain the obvious discrepancies between what he had read to us and the physical evidence. Khal and another tall man, with a turban wrapped around his head, arrived shortly. “Khal,” I asked, “where are the bolts, the pulleys, the ropes, and why is the toilet in the wrong place?” Khal nervously responded that I must have misunderstood. I knew that I had not misunderstood a thing. Every word of that description was seared into my memory.

I called Traci Goins and asked her to tell me what she remembered from the description Detective Khal had read to us. She recounted the bolts, the ropes, the pulleys, slung over the toilet behind the door, and then over the bathroom door. I informed Traci that none of the physical evidence lined up with the written explanation that Rick had heard, that she had heard, and that I had heard from Detective Khal.

Khal and the man with him looked upset and kept trying to recreate different scenarios of how Shane could have hanged himself. As they were conjecturing, John tested each of the scenarios, and nothing they came up with would have been physically possible…

We lingered in Shane’s apartment from morning into the late evening trying to find any clues about what had happened to our son. We kept prodding one another to continue searching: “Surely Shane would have left a clue.”

As we packed up some of Shane’s things to take home, I came across what appeared to be a little speaker for a MAC computer. “Do you think one of the boys could use this?” I asked Rick.

“Throw it in the bag,” he responded.

It wasn’t until weeks after Shane’s funeral that Rick plugged in that “MAC speaker” and discovered that it was not a speaker at all, but an external hard drive with thousands of files backed up from Shane’s computer. The data revealed by those files began to transform this story from a tragic suicide to an international saga of mystery, deceit, and cover-up involving three countries.

Tomorrow: Part II.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login