Special to WorldTribune.com

Forty years ago, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping made a celebratory tour of the United States in the wake of the U.S. recognition of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Deng’s trip from Jan. 28 to Feb. 5, 1979, started in Washington, and made stops in Atlanta, Houston and Seattle.

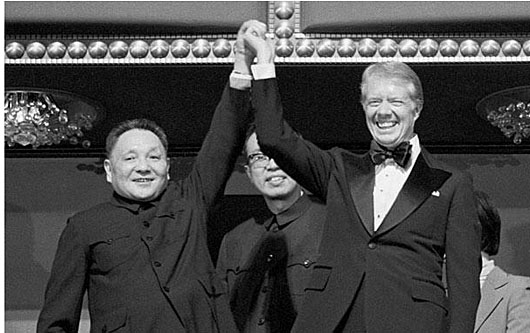

One of the memorable scenes of the trip was a gala in Deng’s honor at the Kennedy Center in Washington in the evening on Jan. 29. The Chinese leader wearing a dark Mao suit and the American President Jimmy Carter in a black tuxedo stood side by side with arms aloft and smiled broadly, as the orchestra played “Getting to know you,” symbolizing the opening of a new era U.S.-PRC friendship and cooperation.

If Carter thought the Chinese connection was a diplomatic coup enabling the U.S. to play “the China card” against the Soviets, he was terribly mistaken and the cost was enormous.

In order to establish full diplomatic relations with the PRC, the U.S. had to accept Beijing’s three demands: to sever official ties with the Republic of China (ROC), the KMT regime in Taiwan, abolish the U.S.-ROC mutual defense treaty, and withdraw U.S. military installations and personnel on Taiwan.

During his stay in Washington, Deng also succeeded in persuading Carter to give “a green light” for China’s invasion of Vietnam, which took place on Feb. 17, less than two weeks after Deng’s return home from the U.S. Deng got more than “moral support” from Carter in Beijing’s plan to “teach a lesson” to Vietnam, the Carter Administration also provided intelligence support to aid China’s war effort in Vietnam.

Deng’s “shopping list” was long. He believed that “technology is the number one productive force” for economic growth, the only way China could surpass the U.S. as an economic power was through massive scientific and technological development, and an essential shortcut would be to take what the Americans had already possessed. Hence, under Deng’s guidance, Fang Yi, Director of China’s Science and Technology Commission, signed agreements with the U.S. government on Jan. 31, 1979, to speed up scientific exchanges.

In the first five years of exchange, some 19,000 Chinese students would study at American universities, mainly in the physical sciences, health sciences and engineering. Their numbers would continue to increase. China’s strategy was to obtain the U.S. assistance in physics, atomic energy, computer science, astronautics and other fields, and an innocent and sympathetic Carter administration complied.

Deng may have thought in 1979 that, with the U.S. cutting official ties with the ROC and terminating the mutual defense treaty, the KMT regime in Taiwan would be so weakened and would readily accept Beijing’s terms of unification.

Deng’s “Taiwan dream” was dashed soon after his return from the U.S. Although Carter de-recognized the repressive authoritarian KMT regime, American people and their representatives in the Congress value the security, freedom and friendship of the 17 million people on Taiwan and try to do what is possible to forestall possible annexation by the Chinese Communists. Much to the chagrin of Chinese leaders, the U.S. Congress enacted in the spring of 1979 the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) over President Carter’s objection.

The TRA is a domestic U.S. law, but it contains provisions which commit the U.S. to Taiwan’s security. More specifically, it stipulates the U.S. obligation to provide Taiwan with “such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary” for Taiwan’s defense, declaring an intention to “resist any resort of force” against the people on Taiwan, and warning Beijing that any such use of coercion to achieve unification would be a matter “of grave concern to the United States.”

Many experts consider the TRA a “function substitute” for the U.S.-ROC Mutual Defense Treaty, which was terminated at the end of 1979, as it has incorporated in substance the same protective relationship the U.S. has maintained with Taiwan since the 1950s. The TRA passed both the Senate and the House by overwhelming, veto-proof margins that Carter had no choice but to sign it as he did on April 10, 1979.

Chinese leaders were enraged, but the PRC was not strong enough militarily and politically to challenge the U.S. then. To absorb Taiwan has been the dream of the Communist leaders since Chairman Mao, but in 1990 Deng called on the party cadres to keep low profile, bid for time, observe the principle of strategic patience and work hard to prepare for the opportune moments.

However, from time to time, some hawkish military officials have ignored Deng’s advice and ventured to confront the U.S. over Taiwan.

In October 1995, Gen. Xiong Guankai, the deputy chief of general staff of China’s military and its chief of military intelligence told a retired U.S. State and Defense Department specialist on China Charles Freeman Jr. that China was prepared to sacrifice millions of people, even entire cities, in a nuclear exchange to defend its interests in preventing Taiwan’s independence. “You will not sacrifice Los Angeles to protect Taiwan,” Xiong told Freemen. Was Xiong bluffing? It was a typical Communist psychological warfare to intimidate and deter the U.S. from defending Taiwan.

The U.S. was not intimidated, however. In December 1995, the American aircraft carrier NIMITZ sailed through the Taiwan Strait, with a cruiser, a destroyer, a frigate, and two support ships to counter the Chinese campaign of threats and intimidation. It was the first time any American aircraft carrier had appeared in the Taiwan Strait since Deng Xiaoping’s U.S. trip in 1979.

By this time, Deng was already out of China’s policy-making structure, and some militant elements in the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) decided to test the U.S. determination. In February 1996, a month before Taiwan’s presidential election, the PLA massed about 150,000 troops along China’s southeastern coast for live-fire military exercises. On March 8, two weeks before people in Taiwan were to cast their votes for the first time to elect their president, the PLA test-launched missiles targeting the vicinity of Kaohsiung and Keelung, the two major port cities of Taiwan.

The Chinese Communists strongly disliked Taiwan’s process of democratic changes under President Lee Teng-hui, a native of Taiwan, with a Ph.D. from Cornell. To some PLA leaders, for Taiwan’s millions of voters to elect their president was virtually a declaration to the world of Taiwan independence, in defiance of Beijing’s repeated claim that Taiwan is a province of China. The PLA military exercises, including firing missiles straddling both sides of Taiwan were designed to create economic, social and political turmoil in Taiwan, disrupt the presidential election and help defeat candidate Lee.

The American response was swift, firm and decisive. Defense secretary William Perry warned a visiting ranking PRC diplomat that any military action against Taiwan would have “grave consequences” for China.

On March 9, the U.S. decided to deploy two aircraft carrier groups in the waters near Taiwan, an important decision proposed by Perry and approved by President Bill Clinton to present China with an overwhelming display of U.S. military force during the confrontation over Taiwan.

The INDEPENDENCE and NIMITZ aircraft carrier battle groups, with dozens of warships, were the largest concentration of American naval power in East Asia since the Vietnam War. Its mission was a “preventive defense” but the U.S. was ready, if necessary, to use force to stop China’s egregious actions. Faced by much superior U.S. forces and shocked by powerful U.S. intervention, the PRC backed down quickly and an international crisis was averted.

In fact, China’s threat of force backfired. Lee Teng-hui, the Taiwanese leader Beijing sought to unseat, was elected with a 54 percent popular votes.

The U.S. action was a clear reaffirmation of the U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan under the TRA. In April 1996, soon after the Taiwan crisis, President Clinton visited Tokyo and signed a new agreement with Japan to extend, broaden and solidify the U.S.-Japan security agreement.

Since his rise to power in China, Chairman Xi Jinping has been promoting a grand strategy to challenge the Pax Americana and a “China Dream” to absorb Taiwan. His New Year offer of unification, through threat of force and incentives, was resoundingly rejected by both Taiwanese people and President Tsai Ing-wen. Taiwan is an independent and democratic polity, Taiwanese people reject Beijing’s offer of so called “one country, two systems.”

Likewise, the U.S. has unveiled National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy to counter China’s rising hegemony, deter China’s economic and military aggression, and safeguard security in the Indo-Pacific region, including the U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan. The U.S. is boosting security ties with Taiwan and its policy to help Taiwan defend itself is in the U.S. national interest, mandated by the TRA.

Xi Jinping should make no mistake.

Dr. Parris Chang has served on Taiwan’s National Security Council. He is professor emeritus of political science at Penn State University and President of the Taiwan Institute for Political, Economic and Strategic Studies.