Special to WorldTribune.com

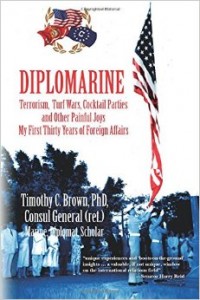

[Following is a second excerpt from the new book, DIPLOMARINE]. See first excerpt: Terrorism and cocktail parties.]

Timothy C Brown, PhD.

There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of books on America’s foreign policies as seen from virtually every angle save one — that of the poor bastards charged with trying to make them work. In ‘Diplomarine’ I try to fill this gap, at least partially, by telling what the world of foreign affairs looked like to me from the bottom up over a course of thirty years, first as an enlisted Marine and then as a career diplomat.

Few people outside those directly involved realize that the Cuba embargo [was] governed by a World War I law, the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act, that gives the President the power to enforce it or not. . . . So every President since 1960 had the authority to end it, but none did. Each did, however, have a different position when it came to its implementation.

When, in 1981, Reagan gave orders to tighten it, the job of complying with his orders fell to the State Department, which is where it became my job to find ways to follow his orders, not ways to obstruct his decision.

We’d already pretty much emptied our quiver of bilateral measures, so at first I couldn’t see how that could be done. Then one afternoon an idea popped into my head. If there weren’t more ways we could screw the Cubans directly, why not screw them indirectly via our friends who were still trading with them, which pretty much included everyone.

After a bit of discussion . . . we took it to Tom Enders, then Assistant Secretary of State for the Americas. Enders didn’t just like it. He loved it, mostly because the Canadians would be among those we screwed. I never did learn what he had against the Canadians, but he was a former Ambassador to Canada, so they must have pissed him off while he was there, and he wanted to get even. Regardless, green light flashing brightly, I went hunting for friends to screw.

My first step was to collect data on what Cuba was exporting to other countries, which turned out to be mostly sugar, nickel, cigars, tobacco and AK47s. There wasn’t much we could do about the AK47s. But we could do something about the others. The question was how to “persuade” our friends to stop buying stuff from Cuba, or at least get them to reduce their purchases. The answer was to extend the embargo to include products being imported into the United States from them that had so much as a smidgen of whatever they were importing from Cuba. For example, it takes lots of sugar to produce Canadian Club whiskey and Polish hams, and both Canada and Poland were buying sugar from Cuba, which was OK as long as not so much as a granule of Cuban sugar was used to produce what they exported to us.

I still remember an especially poignant letter from the distillers of Canadian Club assuring us, cross their hearts and hope to go broke, that they meticulously excluded Cuban sugar from the whiskey they exported to us. They did, however, complain that having to do this was a bit of a pain in the ass. As a former commercial officer, I could feel their pain. So I tried to be helpful by suggesting one way to make sure they were complying would be to put radioactive isotopes in whatever Cuban sugar they bought so we could trace it, just in case. Maybe they could even use that as an advertising slogan: “Drink Canadian Club—You’ll Glow in the Dark.” But for some reason they didn’t cott on to the idea, perhaps because their marketing people thought that the risk of glowing in the dark after imbibing radioactive isotopes along with their booze might unsettle some of their customers.

Nickel was easier. Behind the headlines, a constant exchange of information takes place between embassies in Washington and the State Department. Mostly this is just a way for each to keep the others informed about what’s going on, so one of the routine chores of a Desk Officer is to meet with officers from foreign embassies. While I was on the Paraguay/Uruguay Desk, no Embassy in Washington seemed interested in our relations with either country. But they all seemed to want to know what was up between us and the Cubans, including with regards to the embargo because of its impact on their commercial interests. In diplomacy just like in real life, money matters.

Job finished, or so I thought, I began to relax until out of the blue, the personal aide to one of the State Department’s new senior officers called me to say his boss wouldn’t sign it, because the recommendations in it were appalling and completely unacceptable. I was shocked, especially because his boss was a brand-new Reagan political appointee, so I pressed him,

“Are you sure?”

“Yes!”

“Have you talked to your boss about it?”

“I don’t have to. I know how he thinks, and he’ll never agree!”

“Really?”

“Yes!!

“Are you absolutely sure?”

“Yes, absolutely!!!”

Finally, realizing that my attempts to engage him in cheerful repartee were just making him more and more angry, I said I’d be right down to talk with him about it. At first he insisted he was much too busy to see me. But when I persisted, he said,

“It’ll be a waste of your time. But if you insist, come down and I’ll tell you ‘hell no, we won’t go’ to your face.”

My welcome assured, I strolled down to his office. It turned out that he was a political appointee with no experience whatsoever except as a personal lackey of his boss and that he had a particularly low opinion of career FSOs. The harder I tried, the more he dug in his heels until, in the end, he flatly refused even to send the paper into his boss.

At that point I was so pissed, to keep myself from punching his lights out, I did a smart about face and walked out. Several Foreign Service colleagues who worked in his office told me later that he’d been extremely pleased with himself and had started strutting around the office gloating about how he’d faced down yet another “striped pants cookie-pushing State Department leftie,” implying that they should take their cue from what he’d done to me and stay out of his way. His victory dance lasted about fifteen minutes. I was so steaming mad that the minute I got back to my office I called Lyn Nofziger on his direct line and asked cheerfully,

“Why in the @#* did you appoint a Castro-loving leftist mole to take over Economic Affairs? I just had a run in with his aide and he’s softer on Castro than anyone I’ve ever met! The @#*er is trying to block the tightening of the embargo we talked about just last week.”

Lyn burst out laughing and asked me what had happened, so I told him. About five minutes after we hung up, my phone rang. It was Reagan’s appointee calling me personally to congratulate me on the brilliant ideas in the memo, all of which he enthusiastically supported, although he had a few more ideas and wanted to discuss them with me if I could spare a few minutes to come down to his office. I promptly did so. As his aide stood by with a stunned look on his face, I explained that everything in it had already been approved by the White House and suggested he just sign it and present his new ideas later.

As an aside, the Cuba Embargo is a sterling example of myth trumping truth. The myth is that, because of the embargo, the United States does not engage in commercial trade with Cuba, and because we don’t, try as they might, the Cubans have been unable to grow their economy. The truth is that every country in the world, from Canada to China, with the sole exception of the United States, has always traded with Cuba and so have we, albeit on an embargo-restricted scale. In fact, an important part of my job was to review and approve licenses authorizing the export of certain goods to Cuba, including any health-related items they couldn’t get somewhere else in a timely fashion. There were also exceptions for items related to such things as air-traffic safety, search and rescue operations, and related communications.

Dealing with the Japanese was especially enjoyable, because every month the same junior officer from the Japanese Embassy would invite me to lunch to pump me for information, and I love Japanese food. One of our meetings took place shortly after we began looking for ways to tighten the embargo. Since nickel is a major Cuban export and is used in all sorts of manufactured products, I’d asked one of the national labs if there was a way to determine whether nickel of Cuban origin, even if just a trace, was in a given product. To my surprise, they gave me a qualified yes. Using gas chromatography you can spot even trace quantities of Cuban nickel because it contains markers that identify its place of origin. So during one of our lunches, between bites of superb sushi, I casually commented that we had a new system that could tell us if a product entering the U.S. contained Cuban sugar or nickel, although we wouldn’t be able to tell pre-embargo nickel from post-embargo nickel.

When he looked rather quizzical (his English wasn’t all that good, but more likely he didn’t want to believe what he’d just heard), I explained that, for example, we’d be able to spot an automobile with bumpers that contain even a tiny trace of Cuban nickel and stop it from entering the U.S. The same would hold true, or course, for other things, like computer parts and electronic devices. That afternoon he called me seven or eight times to clarify certain points about what we might do. I assumed he was preparing a reporting cable to Tokyo. Shortly thereafter,

just as we’d expected, the price of Cuban nickel suddenly dropped, since risk reduces market value.

To give my readers a taste of the sort of daily back and forth that goes on between the State Department and our missions on the embargo, I’m including below the text of a once SECRET/EXDIS, now declassified cable I wrote. Addressed to Ambassador Mansfield in Tokyo, it was part of our effort to use nickel as a lever to increase embargo pressure on Cuba via one of our friends, in this case Japan (EXDIS stands for Exclusive Distribution – transcribed from the original by the author)

“[SECRET—DECLASSIFIED AND RELEASED IN FULL]

DRAFTED BY ARA/CCA: TCBROWN: EN

APPROVED BY EA: JHOLDRIDGE

ARA: TENDERS

ARA/CCA: MBFRECHETTE [to protect their privacy, I’ve removed names]

P 022111Z AUG 82

FM SECSTATE WASHDC

TO AMEMBASSY TOKYO PRIORITY

S E C R E T EXDIS STATE 214469

EXDIS [DECAPTIONED]

E.O. 12356: XDS-3, 7/28/2002 (HOLDRIDGE, JOHN H.)

TAGS: ESTC, CU, JA

SUBJECT: CUBA EMBARGO: NICKEL AND JAPAN

FOR AMBASSADOR MANSFIELD FROM ASEC HOLDRIDGE

1. (SECRET ENTIRE TEXT).

2. THE UNITED STATES HAS RECENTLY ENTERED INTO CERTIFICATION ARRANGEMENTS WITH FRANCE AND ITALY TO ASSURE THAT CUBAN NICKEL IMPORTED BY THOSE COUNTRIES DOES NOT SUBSEQUENTLY ENTER THE US IN VIOLATION OF THE CUBA EMBARGO. THESE ARRANGEMENTS COVER BOTH NICKEL AS SUCH AND NICKEL CONTAINED IN MANUFACTURED PRODUCTS SUCH AS STAINLESS STEEL OR CHROME.

3. WE HAVE NOT YET ASKED JAPAN TO ENTER INTO A SIMILAR AGREEMENT EVEN THOUGH JAPAN IS A MAJOR PURCHASER OF CUBAN NICKEL AS WELL AS AN EXPORTER TO THE US OF ITEMS CONTAINING NICKEL. THERE ARE INDICATIONS THAT JAPAN, IF ASKED, MIGHT CHOOSE TO STOP IMPORTING CUBAN NICKEL RATHER THAN ENGAGE THE US FORMALLY REGARDING OUR EMBARGO RELATED CONCERNS. YOU SHOULD SEEK AN EARLY OPPORTUNITY TO MAKE THE FOLLOWING POINTS TO THE APPROPRIATE CABINET LEVEL INTERLOCUTOR.

4. WE ARE SERIOUSLY CONCERNED WITH CUBAN ACTIVITIES CONTRARY TO OUR NATIONAL INTERESTS AND IN THAT CONNECTION MAINTAIN AN EMBARGO AGAINST CUBAN EXPORTS TO THE US IT IS ILLEGAL FOR ANY CUBAN PRODUCT TO ENTER THE US DIRECTLY OR THROUGH A THIRD COUNTRY, EVEN AS AN INPUT TO FINISHED PRODUCTS OF ALMOST TOTALLY NON-CUBAN ORIGIN.

5. IN REGARD TO CUBAN NICKEL WE ASCERTAINED THAT IT WAS BEING INCLUDED IN PRODUCTS ENTERING THE US FROM THIRD COUNTRIES, AND WE HAVE CONCLUDED RATHER COMPLEX CERTIFICATION AGREEMENTS TO STOP SUCH IMPORTS FROM FRANCE AND ITALY.

6. WE HAVE NOTED THAT JAPAN IS AN IMPORTANT IMPORTER OF CUBAN NICKEL AS WELL AS AN IMPORTANT EXPORTER TO THE US OF MANUFACTURED GOODS CONTAINING NICKEL. WE HAVE BEEN GIVING SOME CONSIDERATION TO ASKING JAPAN TO ENTER INTO A SIMILAR ARRANGEMENT. WE UNDERSTAND JAPAN HAS COMPLETED ALL ITS 1982 NICKEL PURCHASES FROM CUBA. DOES JAPAN PLAN TO MAKE ANY FUTURE PURCHASES FROM CUBA THIS YEAR OR 1983, 1984 OR BEYOND?

SHULTZ”

Another case involving a Spanish electronics company was even more dramatic. It was building a large semiconductor plant in Cuba. While that wasn’t a welcome development, as long as they didn’t use American products to do so, it wouldn’t violate the embargo. But when we took a closer look, lo and behold, they were not only using American patents, they were secretly shipping American-made manufacturing equipment to Cuba, including some items of strategic concern. At first, rather than acting immediately we simply let them know that we were aware of what they were doing, giving them an opportunity to change their ways. But they didn’t. So the day before the plant in Cuba was to be dedicated, we designated the company as an Enemy Agent under the Trading with the Enemy Act. While this may sound rather ho-hum, it was anything but. Let me put some flesh on it.

Designation as an Enemy Agent has a ripple effect. It does not make the designee an outlaw. But, once it is designated, any “American person” that deals with it is committing a felony and is subject to criminal prosecution. The company had an office in Chicago, so shortly after it was designated, its Chicago office manager called me to ask what it meant. My answer was simple. Henceforth, no company that operates in the US can legally deal with your company. When he then said he’d been asked by his headquarters to go to Europe to discuss the problem, I asked him how he planned to travel, since it would be a felony violation of the Trading with the Enemy Act for an airline that flies to the US to sell him a ticket.

“Then I’ll fly from Canada,” he said.

“How do you plan to pay for your ticket?”

“I’ll use my credit card.”

“I hope it’s not American,” I said, “because letting you withdraw company funds from a bank to pay your monthly bill will be a felony, too.”

Not surprisingly, his tone of voice began to change from “damn the bureaucracy, full speed ahead” to one that was less certain and a bit more nervous. So I asked him a few more questions.

“How are you going to operate when the water company can’t sell you water, the electric company can’t sell you electricity, the phone company can’t let you make calls, and the janitors can’t even clean your office?”

By then he was thoroughly shaken,

So how can I do my job?”

My answer was simple,

“You can’t.”

After a suitably pregnant silence, I suggested that he contact the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the Treasury Department and ask for a special license. “Although you’d better move fast, because your company may be going bankrupt.”

Frankly, I was privately appalled by the ability of the United States government to put a company out of business without so much as a by your leave. But that’s how it worked. While it was a large company, it was not terribly important to Spain on the national level, so we expected the political fallout from our designating it as an Enemy Agent to be minimal, and were right. And, in any case, its attempts to bypass the Cuba embargo were so extraordinarily blatant that our taking action was easy to defend and had little effect on our bilateral relations.

More information about ‘DIPLOMARINE: Terrorism, Turf Wars, Cocktail Parties and Other Painful Joys My First Thirty Years of Foreign Affairs’ can be found at the author’s site at Diplomarine.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login