Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk

By Donald Kirk

President Moon Jae-In almost accidentally stepped into a battle that did not have to happen with journalists for foreign news organizations.

The ruckus was all about a Korean reporter for Bloomberg who wrote in September that Moon sounded like a spokesman for Kim Jong-Un by singing the praises of the North Korean leader in a talk at the prestigious Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

So what? People say worse things every day about Moon and those around him. People also say worse about the people who say worse things about Moon. In this political climate, in which Moon is pursuing a controversial policy of reconciliation, snide remarks from one side to the other and back again are to be expected.

Moon’s advocates may say how unfair, unhelpful is any criticism against him. The Bloomberg barb was not altogether unreasonable, however, considering that another Moon, Moon Chung-In, the President’s loquacious foreign policy adviser, sounded a bit as if he too were taking Kim Jong-Un’s viewpoint in a talk at which he was besieged by questions from Korean journalists seated on either side of him.

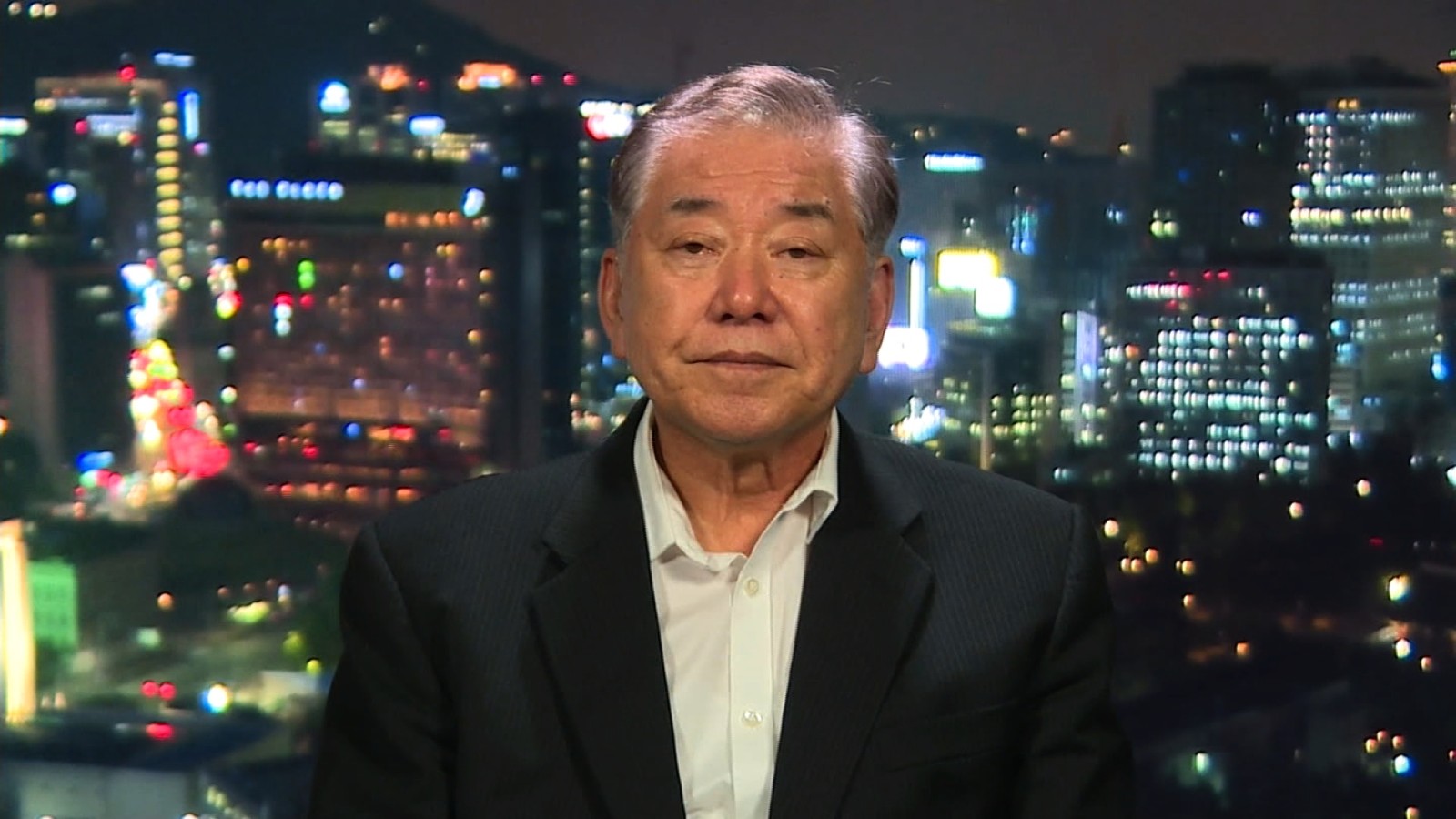

Moon Chung-In had just returned from three days in Washington at which he had absorbed a range of views from American think-tankers about the failed Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi.

Ironically, under skeptical questioning by one of the journalists next to him on the panel, he turned on her and said she sounded like “a spokesman” for the U.S. No one seemed to mind when the “spokesman” label was applied for expressing a pro-American view.

All this repartee was great until leaders of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) were awakened to the fact that the Bloomberg reporter six months ago had had the temerity to reflect, very briefly, the same skepticism as many others in Seoul and Washington. Her story wasn’t noticed until the floor leader of the opposition Liberty Korea Party quoted it in a speech.

Then all hell broke loose. The headline on the story ― “South Korea’s Moon Becomes Kim Jong Un’s Top Spokesman at UN” ― attracted the most attention. That was enough for the DPK spokesman to accuse the reporter of “treason” even though she probably hadn’t written the headline. All that loose talk, though, returned to haunt the DPK, when the Seoul Foreign Correspondents’ Club and then the Asian American Journalists’ Association (AAJA) came out in heated defense of the beleaguered reporter.

Amid back-pedaling and even apologies, the powers-that-be, that is the ruling establishment, both party and government, seem to realize they made a mistake in pillorying a reporter for a single, brief, largely forgotten, story.

The Candlelit Revolution was about a lot of things ― corruption, power-grabbing and influence-buying ― but it was also about freedom of expression, freedom of the press, debate from both sides. President Moon, of all people, should recognize the basic principles that enabled him to take over the government in the spirit of justice and democracy.

In that same spirit, Moon and those around him must recognize that reconciliation with North Korea, while noble in the abstract, may not work out in practice. Knowledgeable people, ranging from veteran diplomats to business leaders to academic figures, not just the rightwing flag-wavers who parade through central Seoul every Saturday, are pointing out the flaws inherent in his policy.

Moon Chung-In, a retired Yonsei University professor, energetically calls for “steps” to be made by both sides but fails to recognize that North Korea has dishonored all its agreements. He never stops talking up an end-of-war declaration and peace treaty as if those words on paper would have real meaning nearly seven decades after the Korean War ended.

Moon Jae-In, not Moon Chung-In, may still bring about a measure of reconciliation through talks on different levels. By the time he steps down three years from now, we may see clear signs of rapprochement in the form of cultural exchanges, regular reunions of divided families and humanitarian programs. Sanctions may be eased, making it possible to reopen the Gaeseong Industrial Complex and the Mount Geumgang tourist zone.

One way not to achieve any of these goals, however, is to attack some wayward reporter for the kind of jibes that one has to expect in a democracy. Moon probably understands that. Nobody wants to see South Korea revert to the bad old days of intimidation of the media in the name of any belief, including reconciliation with a totalitarian state within artillery range of the Blue House

Donald Kirk has covered the Korean democracy struggle since the 1970s.