Special to WorldTribune.com

By Donald Kirk, East-Asia-Intel.com

The specter of Park Geun-Hye running for president of the Republic of Korea evokes almost as many memories for those foreigners who were here during the reign of her father as it does for millions of Koreans who share quite differing perspectives.

As a journalist in pursuit of about the only story that interested American and British editors at the time, I rushed for interviews all over Seoul with foes of the regime. You had only to tell a taxi driver outside the Chosun Hotel that you wanted to see Kim Dae-Jung, and he sped you over to his residence in Mapo-gu. DJ loved to talk to just about anyone who called — not exactly the response I got when he was president and his aides shielded him from those who might be critical.

We didn’t ask much in those days about the economy other than to get a few pro forma briefings on the five-year plans that Park Chung-Hee was dictating for the benefit of the rising leaders of Korea’s future global business empires and the bureaucrats dedicated to their success.

We were far more interested in Park’s record of suppression of human rights. The Korean “economic miracle” was a story for public relations people and business writers. We noticed more cars on the streets but weren’t exactly clamoring to meet the people who produced them.

The fact is, however, many Koreans view Park as Korea’s best president, the man who did the most to lift the country from the abyss of poverty into which it had sunk during the Korean War. He’s credited with spurring the chaebol chieftains to wealth and success, convincing them Korean products could rival those from anywhere else, notably Japan, Korea’s historic foe, and the U.S., her latter-day ally.

All of which puts Park’s daughter in a difficult position. If she defends the record of her father, even on business and economics alone, she opens herself to outcries of lack of concern for all those who suffered during his rule. And if she criticizes him, then Park’s old-time admirers accuse her not just of political opportunism but of betrayal of the man who made Korea great.

In a sense this debate over the rights and wrongs of the Park era is edifying. Koreans should think about their country’s epic history and Park’s record of building the economy while stifling criticism, often harshly. Could Korea have become what it is without a president such as Park? Or would Korea have emerged as a greater country if a liberal or leftist had ruled for the 18 and one half years in which Park held sway?

In those days when Park was riding high, foreign missionaries and teachers were among his biggest critics. They loved to give interviews on the sins that he had committed against critics of his “Yushin” constitution. They crusaded against the government for its offenses against academic freedom and repression of workers battling for fair wages and benefits and the right to unionize new factories rising from swamps, fields and forests all over the country.

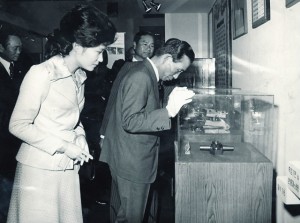

Park Geun-Hye had a ringside seat on all that was going on. When her father seized power on May 16, 1961, she was nine years old, 10 by Korean age. She grew to be an adult in the Blue House. When her mother was assassinated on Aug. 15, 1974, by a bullet intended for her father, she was 22 or 23, depending on how you count it. For the next five years, until her father was assassinated on Oct. 26, 1979, she was First Lady. She has to have known a lot about how her father operated, what he did to build up Korea while beating up his enemies.

Like many Koreans, a lot of foreigners whom I knew in this period have trouble explaining how Park could have done so much for his country while trampling all over the human rights of his people. In those days, I don’t recall any of those missionaries and academics sorting the good and bad. They saw Park as all bad.

Park Geun-Hye, from a viewpoint of a foreigner, is an enigma. One wonders what she thought about the rule of the general who seized power some months after her father’s death. Would she defend Chun Doo-Hwan, later convicted along with his successor, General Roh Tae-Woo, for massive corruption and the massacre of about 200 mostly young people in the Gwangju revolt? What was she doing at the time?

Despite such questions, Park doesn’t give an impression, superficially, of wanting to perpetuate her father’s style of governance. She may be conservative but she’s not exactly “rightist” or reactionary. You don’t hear foreign academics attacking her as they did her father. Her mother, Yook Young-Soo, was liked and respected. She seems to have inherited some of the same endearing qualities.

Park Geun-Hye’s father was one of those complicated figures of history, for better and for worse.

Her candidacy inspires introspection into how Korea got where it is and why. In the end, however, Park has to run on her own record in one of the more interesting out of the six presidential campaigns since the “democracy” constitution was promulgated in June 1987 amid revulsion over the dictatorship her father had made.